For years, scientists studying earthquake risk in northwestern Turkey have known where the North Anatolian fault runs but not exactly how it behaves beneath the Marmara Sea. That uncertainty has mattered. The offshore section lies close to Istanbul and has not ruptured in a major earthquake for more than two centuries. A new study now adds detail where there was little before. Using electromagnetic signals recorded on land and beneath the sea, researchers have built the first three-dimensional image of the fault zone below the Marmara Sea. The results do not predict when the next earthquake will happen. They do, however, show clear differences in rock strength at depth and help explain how stress may be building along different parts of the fault system.

Turkey’s earthquake risk is shaped by plate motion

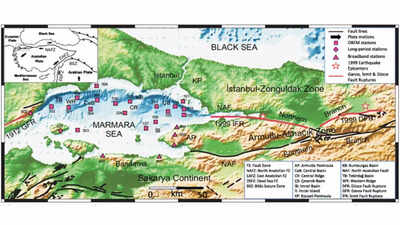

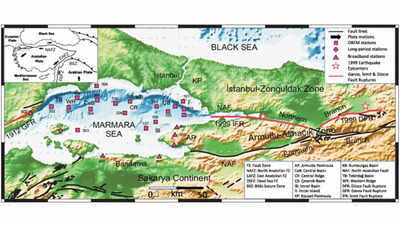

According to the study published in GeoScience World titled, ‘3-D electromagnetic imaging of highly deformed fluid-rich weak zones and locked section of the North Anatolian fault beneath the Marmara Sea’ Turkey sits at the meeting point of several large tectonic plates. The slow but constant movement between them is released through faults that cut across the country. Among these, the North Anatolian fault stands out. It stretches for about 1,500 kilometres and has produced a series of destructive earthquakes over the past century.Since the deadly 1939 Erzincan earthquake, large ruptures have progressed westward along the fault. This pattern has led many researchers to focus on the Marmara Sea, where the fault passes offshore before reaching the Aegean region.

The Marmara Sea fault remains poorly understood

Unlike sections of the fault on land, the Marmara Sea segment is difficult to study. There are few permanent instruments on the seafloor, and standard seismic imaging has limits offshore. As a result, scientists have had only a partial view of the crust beneath the sea, especially at greater depths where earthquakes begin.This lack of detail has made it harder to assess how stress is distributed along the fault and which sections may be more likely to rupture.

Electromagnetic data offers a different view underground

To address this gap, the research team used magnetotelluric data collected from more than 20 stations in and around the Marmara Sea. These instruments measure natural variations in Earth’s electric and magnetic fields. The signals change depending on how easily electricity flows through rocks below. By combining these measurements in a three-dimensional inversion model, the researchers produced an image of electrical resistivity down to tens of kilometres beneath the seafloor.The model shows a patchwork of zones with different properties. Areas with low electrical resistivity are assumed to be fluid-rich and weak mechanically. These zones are typically associated with clusters of small earthquakes, indicating that the stress there might be released more gradually. On the other hand, high resistivity areas seem to be stronger and more rigid. Such sections are probably locked, thus allowing the stress to accumulate over time instead of gradually slipping.One of the study’s major findings is that the boundaries between these different zones play a crucial role. Similar patterns have been noticed along other major faults worldwide. The boundaries in the Marmara Sea may be involved in the initiation of large rupture events. Instead of identifying a single hazardous spot, the findings point towards a segmented fault system with different behaviours along the length of the fault.

Improving hazard assessment near Istanbul

The study does not offer short-term forecasts. Its value lies elsewhere. By clarifying how fluids, rock strength and fault structure interact beneath the Marmara Sea, it improves understanding of how the North Anatolian fault works offshore. For a region facing significant seismic risk, that clearer picture may quietly shape future hazard assessments and preparedness efforts.