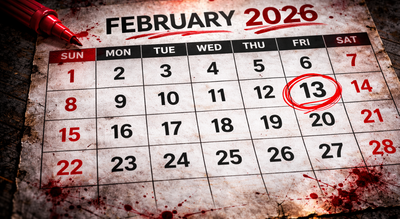

Today, 13 February 2026, falls on a Friday, a pairing that, in many Western cultures, carries an air of unease. For some it is a joke; for others, a genuine source of anxiety. The date has inspired secret societies, horror franchises, stock market thrillers and not one but two tongue-twisting clinical terms: paraskevidekatriaphobia and friggatriskaidekaphobia. It is a superstition at once familiar and strangely persistent, as recognisable as a black cat crossing your path, walking under a ladder, opening an umbrella indoors or breaking a mirror.

A date with an ominous reputation

Friday the 13th occurs when the 13th day of a month in the Gregorian calendar lands on a Friday. It happens at least once every year and sometimes as many as three times. On average, one arrives every 212.35 days. In 2026, there are three: Friday, 13 February; Friday, 13 March; and Friday, 13 November. By contrast, 2025 had just one, in June. For a subset of people, the date provokes genuine distress. Psychotherapist Donald Dossey coined the term paraskevidekatriaphobia, from the Greek Paraskevi (“Friday”), triskaideka (“thirteen”) and phobos (“fear”), to describe an intense, sometimes paralysing dread associated with the day. Another term, friggatriskaidekaphobia, combines Frigg (the Norse goddess from whom Friday takes its name) with triskaidekaphobia, the fear of the number 13 itself. Anxiety around the date can produce physical symptoms: increased heart rate, sweating, rapid breathing and trembling. Researchers have estimated that as much as 10 per cent of the US population harbours some fear of the number 13, according to reporting cited by The History Channel. Yet the precise origins of the superstition remain elusive.

Across cultures and beliefs, where did it all began?

Historians struggle to pinpoint a single source. References linking Friday and the number 13 appear in 19th-century France. An 1834 article in the literary magazine Revue de Paris, written by Italian author Marquis de Salvo and titled “Le Chateau de Carini,” mentions a Sicilian count who murdered his daughter on Friday the 13th, declaring: “It is always Fridays and the number 13 that bring bad luck!” That same year, in the French play Les Finesses de gribouille by Claude-Louis-Marie de Rochefort-Luçay and Philippe-François Pinel Dumanoir, a character laments: “I was born on a Friday, December 13, 1813, from which come all of my misfortunes.” Stephanie Hall, a specialist at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, has suggested that the superstition may have grown from the idea that Fridays and the number 13 were independently considered unlucky, and may initially have referred specifically to Friday, December 13. The number 13 itself had long attracted suspicion. In Norse mythology, Loki, the trickster god, arrives uninvited as the 13th guest at a banquet in Valhalla, where he manipulates events leading to the death of Balder, the god of light. In Christian tradition, Judas Iscariot, whose betrayal preceded Jesus’ crucifixion on Good Friday, is often described as the 13th guest at the Last Supper. Biblical narratives also attach misfortune to Friday: Adam and Eve are said to have eaten the forbidden fruit on a Friday; Cain is believed to have murdered Abel on a Friday; the Temple of Solomon was destroyed on a Friday; and the Great Flood is said to have begun on a Friday. Some scholars point to numerology. Speaking to National Geographic, Thomas Fernsler, an associate policy scientist at the Mathematics and Science Education Resource Center at the University of Delaware, noted that 12 has historically symbolised completeness, 12 months, 12 zodiac signs, 12 gods of Olympus, 12 labours of Hercules, 12 tribes of Israel, 12 apostles. Thirteen, arriving just beyond that tidy order, “has to do with just being a little beyond completeness. The number becomes restless or squirmy,” he said.

The Thirteen Club and other rebellions

Not everyone accepted the curse. In 1882, former Union captain William Fowler founded the Thirteen Club in New York to dismantle superstitions surrounding the number. The group met on the 13th day of each month, dined in room 13 of the Knickerbocker Cottage and ate 13-course meals. Members deliberately spilled salt without tossing it over their shoulders and opened umbrellas indoors. Before dining, they walked beneath a ladder beneath a banner reading “Morituri te Salutamus,” Latin for “Those of us who are about to die salute you.” Four US presidents, Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison and Theodore Roosevelt, were honorary members at various points. Friday the 13th also entered fiction. In 1907, Thomas William Lawson published the novel Friday, the Thirteenth, about a stockbroker who manipulates superstition to trigger panic on Wall Street. Decades later, the 1980 horror film Friday the 13th introduced audiences to Jason, the hockey mask-wearing killer, spawning 12 films and cementing the date’s pop-culture status. Some link the superstition to Friday, 13 October 1307, when King Philip IV of France ordered the arrest of hundreds of the Knights Templar. The theory remains contested; historians describe the connection as murky.

Around the world: Variations on a theme

The fear is often described as Western-centric, but its shape shifts across cultures. In Spain and Greece, Tuesday the 13th is considered unlucky, combining the number with Mars, the Roman god of war, from whom the Spanish word martes (Tuesday) derives. In Italy, anxiety centres on Friday the 17th; the Roman numeral XVII can be rearranged to spell VIXI, Latin for “my life is over.” In Japan and China, the fourth day of the fourth month is feared because the pronunciation of the number four resembles the word for “death.” India has its own associations. In Hindu mythology, Rahu, originally an asura named Rahuketu, drank nectar during the churning of the ocean (Samudra Manthan) after disguising himself as a god. Vishnu, in the form of Mohini, severed his head with the Sudarshana Chakra before the nectar passed his throat. The head became Rahu and the body Ketu, both later considered planetary entities. Rahu is sometimes referred to as the 13th immortal, linking the number symbolically to cosmic disturbance.

Still here, and still observed

For many today, Friday the 13th is less omen than occasion. Tattoo studios in parts of the United States and Europe offer discounted “flash” tattoos, a tradition that gained popularity in the 1990s. Others mark the day with horror film marathons or by deliberately testing minor superstitions. Yet behaviour does shift. Some people postpone travel or business decisions; some buildings skip a 13th floor; airlines occasionally note dips in bookings. And while there is no empirical evidence that Friday the 13th brings misfortune, the persistence of the belief suggests something deeper: a human tendency to impose narrative on coincidence. The date arrives, as it always does, as a quirk of the Gregorian calendar. Whether it carries dread, delight or indifference depends less on the stars, and more on what we choose to see in them.