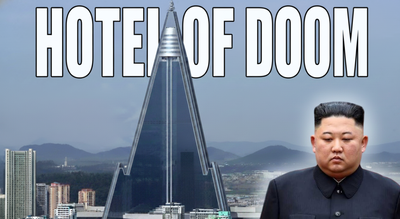

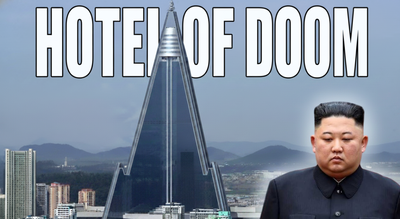

From most angles in Pyongyang, the Ryugyong Hotel looks finished and ready for guests. The glass skin is smooth, the 330-metre pyramid sharp against the skyline, its tip tapering into a neat, futuristic point. This is North Korea’s tallest building, rumoured to have 105 storeys and once pitched as a luxury complex with more than 3,000 rooms and five restaurants. Yet nobody has ever stayed there. Behind the glass, much of the interior is still raw concrete. For years, the building has carried nicknames that say more than any brochure: the “Hotel of Doom”, the “Phantom Hotel”, a £600 million (approx. USD 800 million) project that never opened its doors. Very few people from outside the country have seen what it actually looks like inside. One of the exceptions is a British tour organiser called Simon Cockerell.

The man with a key to Pyongyang

Cockerell is Managing Director of Koryo Tours, a Beijing-based company that has specialised in travel to North Korea since the early 1990s. He wasn’t parachuted into the role as a think-tank expert; he backed into it through everyday life.

Simon Cockerell, a veteran North Korea tour director, is among the few Westerners with long-standing, sanctioned access to the country/ Instagram

He was living in China when he met a fellow Brit through an amateur football league in Beijing. That teammate had co-founded Koryo Tours with another Brit, with help from a North Korean businessman who also played in the same league. Cockerell was offered a job, took it, and over the next two decades became one of the most frequent Western visitors to North Korea. Koryo’s own materials note that he has probably been to the country more than any other Westerner. Those connections, built over more than 20 years of sanctioned trips and careful relationship-management, are what eventually got him inside the Ryugyong.

What the hotel was meant to be

North Korea started building the Ryugyong in 1987. At the time, it was meant to signal prosperity: a supertall hotel to rival one being built in Singapore, then on track to become the tallest in the world. The plan in Pyongyang was similarly bold – a pointed, 330-metre tower with three wings, each 100 metres long and 18 metres wide, narrowing into a 40-metre-wide cone at the top.

The pyramid-shaped hotel was designed to reach 300 metres in height and house at least 3000 rooms. (AP)

The country pushed ahead until the early 1990s, then stopped for 16 years when money and materials dried up. The bare concrete frame stood over the capital while the rest of the world moved on. Since construction began, the Berlin Wall has fallen, Nelson Mandela has been released and elected president, and the internet has gone from invention to infrastructure. The hotel, meanwhile, stayed empty. Work restarted in 2008, this time focused on the outside. Glass cladding went on, the concrete disappeared from view and, for a while, there were public forecasts: exterior complete by 2010, interior by 2012. Some observers even speculated about an international hotel group taking over. None of that happened. The exterior reached its current, polished state. The interior did not follow.

The day Cockerell went inside

Cockerell’s visit came during that renewed construction period. His long record in the country meant he was occasionally invited into places tourists only ever walk past. One day, he and a colleague were allowed to approach the Ryugyong, just as work teams were dealing with the last glass on the crane at the top. “The glass cladding that had been put on the crane on the top had been removed by helicopter – I was there when that happened, actually, so I got access to that myself and one colleague along with a couple of people we worked with,” he told LadBible. What he walked into was not a finished luxury lobby. It was a vast, stripped concrete interior: a central space with barriers along each floor edge, unfinished lift shafts and no visible rooms built out. The photographs taken on that visit, later shared by Koryo Tours, show a grand volume with almost nothing in it. It is impressive and eerie at the same time – a building that exists in outline but not in use.

Rare photo from inside Ryugyong. Image Credit: Simon Cockerell | 9News

Inside the hotel on the ground floor. The skyline of Pyongyang can be seen through the glass windows/ Simon Cockerell via 9News

A rare photo from inside Ryugyong. Image Credit: Simon Cockerell | 9News

Cockerell hasn’t been back inside since. From the street, he says, you can sometimes see what looks like a lit lobby floor behind the glass. Whether that’s a genuinely finished level or a dressed-up façade is harder to judge. The country does not invite many people close enough to check.

A heavy, concrete pyramid in a windy world

Part of what makes the Ryugyong so unusual is how it was engineered. Supertall towers are usually steel-framed, to flex slightly with the wind. This one is almost entirely concrete. Concrete is strong, but not very tensile; it doesn’t like being bent or twisted. To make a concrete tower that tall, you need to spread the weight. The Ryugyong’s solution is size. Its footprint is huge, the three wings acting as stabilisers that get slimmer as they climb. That shape – a wide base pulling into a narrow tip – is not just visual theatre; it’s a way to stop the entire structure from becoming a 330-metre problem in strong wind. Rumours grew around the building as the years dragged on. People outside North Korea swapped stories: the concrete was unsafe, the lift shafts were misaligned, the tower might never be usable. Cockerell has heard those claims and tends to treat them as exaggerated. He points out that many buildings in Pyongyang would fail Western safety standards; the Ryugyong’s issues, in his view, are more about money and priorities than a unique engineering disaster. Different projects get different budgets. This one never got enough to finish.

A ‘Hotel of Doom’ in a country that changes slowly

While the hotel has remained static, North Korea itself has changed in ways that can be easy to miss from the outside. Cockerell talks about the proliferation of mobile phones, the rise of a small urban middle class in Pyongyang and the slow shift in what it looks like to show status in public. Two decades ago, flaunting any kind of wealth would have been frowned upon. Today, he sees more variation in clothes, gadgets and private consumption, at least in the capital. The state’s controls are still tight. Most residents have no access to the global internet. Contact with the West is heavily restricted. After Covid-19, the government shut its borders completely, only tentatively reopening this year to Russian visitors and a limited group of tourists running the Pyongyang marathon. Through all of that, the Ryugyong has sat there – lit up from the outside on special occasions, dark and inaccessible on most others. It hasn’t hosted a guest, a conference or even a known test run. For visitors like Cockerell, the building has become a fixed reference point: a giant pyramid that looks finished from a distance, and reveals its emptiness only if you’re one of the rare people allowed to step through the door.

What the tower represents now

There are plenty of skyscrapers in the world that never opened, projects mothballed halfway through when economics or politics turned against them. The Ryugyong is different for a couple of reasons. It sits in one of the most closed countries on earth. It has been part of the skyline since the late 1980s. And it was designed as a showpiece in a capital city that doesn’t have many. Whether the hotel is eventually finished, repurposed or quietly left as a sealed monument is a decision only the North Korean state can make. For now, it remains what Cockerell saw on that day inside: an enormous, echoing concrete shell, built for guests who never arrived.