For those not familiar, the term sigma male is a modern-day Jungian internet archetype used to describe a man who is ostensibly independent, self-assured, and operates outside traditional social hierarchies. Think Tyler Durden, Travis Bickle, or John Wick.Of course, like most internet slang, it has become a parody of its original meaning, with the term used to describe malignant (and often misogynist) internet personalities that appeal to incels. The term was rather in vogue last year after influencers Jake Paul and Andrew Tate lost fights to professional athletes, with some even dubbing the losses “9/11 for sigma males”. Soliloquies on internet culture aside, the losses were a reminder of the gap that exists between regular people and athletes. Like the time billionaire Bill Ackman learnt this while participating in the Hall of Fame Open, where he could barely lay racket on ball.Most non-athletes wouldn’t last in a cage, ring, or court with a professional. But even amongst professional athletes, there’s a rare breed that has access to a metaphorical place their less hallowed peers wish they could reach. They operate at a level that even fellow professionals fail to comprehend. It’s both mental and physical.As Andre Agassi said after his 2005 US Open Final loss to Roger Federer: “In the tiebreak, he goes to a place that I don’t recognize…. I feel for the man who is fated to play Agassi to his Sampras.”Now Agassi is no shrinking violet; he is the first man to win a Career Golden Slam. One of the greatest returners in the game, and yet he couldn’t believe what Federer was doing.During their time, the Big Three showed how they were a cut above the rest. Their dedication to the craft was unmatched. Novak Djokovic has spent the last decade living like a hermit. Rafa Nadal pushed his body to a level that seemed unfathomable, perfectly epitomised by the John McEnroe line: “This kid is sensational, is he going to play every point like that?” Federer, as Agassi observed, looked like he could play a professional match without breaking a sweat, as if he should wear a smoking jacket instead of tennis gear. Federer looked like he was dancing on the court. Nadal covered every blade of grass, every grain of sand, every inch of clay. Djokovic looked like — and still looks like at 38 — he could go on for days, seemingly powered by a perpetual motion machine from another universe.Ivan Lendl, another man who knows his way around the tennis circuit, observed in 2017 while coaching Andy Murray, who was attempting a comeback after hip surgery: “The top guys are top guys because they do things a little bit better than the other guys. Yes, they can get upset, or the others can upset them, but if they play 100 times they are going to win more than half. They are better in stroke production, movement, physically. You put all that into a package and the package is slightly better than the guys below.”

And at Melbourne Park, Carlos Alcaraz reminded us how he is cut from the same cloth as the GOATs before his era.Before the semi-final, the murmur around the Australian Open — and the online chatter that follows it — suggested this had been too one-sided a tournament so far. One that could have been an email instead of a whole tournament because a Sincaraz final looked inevitable. Sinner and Alcaraz met in six finals in 2025, three of them Grand Slams. They have evenly split the last eight majors. And their meeting in the first Slam of 2026 seemed inevitable until it seemed impossible as Alcaraz lay on the floor.We have seen Alcaraz do remarkable things in his career so far. His drop shot can leave opponents wrong-footed. In the last few years, he has made good on his promise to become a serve bot. At times, he hits shots from angles that even cameras cannot catch.Alcaraz was cruising against Zverev with a two-set lead when cramps laid him low. And suddenly, he couldn’t walk, swing, or move at will. His movement was oddly reminiscent of Aussie cricketer Glenn Maxwell against Afghanistan in the 2024 ODI World Cup, where the Aussie was laid low by cramps. But like Maxwell, Alcaraz found a way out.His medical timeout will be discussed ad nauseam. Zverev’s infuriated response has already launched a million reactions on Tennis Twitter. Boris Becker added his two cents, which he is wont to do on issues outside tennis as well.Perhaps the organisers at Slams go out of their way to help the stars, given that it’s their presence that draws the big bucks and eyeballs. But what’s undeniable is that Alcaraz managed to reach into that special fountain of fortitude available only to the greatest players. Zverev’s outrage during the timeout foreshadowed the things to come.

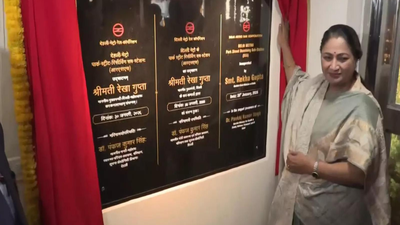

Alexander Zverev of Germany gesturers to a tournament official during his semifinal match against Carlos Alcaraz of Spain at the Australian Open tennis championship in Melbourne, Australia, Friday, Jan. 30, 2026. (AP Photo/Asanka Brendon Ratnayake)

Even after getting back on his feet, Alcaraz could barely keep up. And yet he would not give up. After the match he explained: “I always say you have to believe in yourself, no matter what you’re struggling [with], what you’ve been through, you’ve got to still believe in yourself all the time.”As Lendl had explained: “That’s how people win tournaments — they fight. It doesn’t come easy. You don’t always play your best and you have to get through that and fighting is part of it. When you play, sometimes you feel tired and you have to push through that pain barrier as well…”The Spaniard never stopped believing, and neither did the crowd, even when Zverev was serving for the match at 5-4. But in what seemed like an instant, Alcaraz had his arms aloft, level at 5-5, and suddenly ahead at 6-5.Watching them side by side was watching two responses to pressure unfold in real time. Zverev had the match on his racket, serving at 5-4, physically strong and dictating rallies, a player built to impose order. Alcaraz could barely move an hour earlier, yet he kept reaching for variety — drop shots, angled returns, sudden changes of pace — as if chaos itself were a weapon. One tried to close the door through force. The other kept opening windows through imagination. In the end, it wasn’t the healthier body that prevailed but the player willing to keep inventing solutions when logic said the match was over.One shot summed up the contrast. Appearing to hit a normal return, Alcaraz suddenly feinted a drop shot at 5-5 that seemed to send Zverev crumbling.Zverev is a good player trying to become great. He was the youngest player to debut in the top 20 since Novak Djokovic. He beat Roger Federer on grass when he was 17. At home, Zverev is called Sascha, the Russian diminutive for Alexander the Great, who wept after believing there was no world left to conquer. But as the match progressed, one wondered whether Sascha could conquer the demons in his mind — the ones that need to be exorcised to win a Grand Slam title.Alcaraz, on the other hand, has no such demons. The Career Grand Slam remains the Holy Grail of tennis. Eight men have done it, with four in the Open Era. The youngest so far is Don Budge, who was 22 years and 11 months when he completed it, though it was during an era when tennis was played on two surfaces: grass and clay. The youngest to do it in the Open Era was Rafael Nadal at 24 years and three months.Alcaraz, on the other hand, could become the youngest to complete the set. The ones standing in his way will be his great rival Sinner or Novak Djokovic, who is 38 now but refuses to go quietly into the night and wants to become the first man to win 25 Slams. Time will tell who emerges triumphant, but one thing is for sure: no matter what happens on Sunday, Alcaraz’s renaissance from the face of defeat will live long in the annals of the Australian Open.