Tomorrow’s Union Budget will arrive with its familiar vocabulary—“skilling”, “capacity”, ‘future-ready youth’. Fine. But the Economic Survey 2025–26 has already reminded us of something budgets often forget: Education isn’t a sector you ‘announce’ for one day a year. It’s India’s operating system—and the operating system is only as good as its handovers. In our school education, the leak isn’t at the entry gate. It’s later, when childhood turns into adolescence and schooling turns into logistics—distance, safety, time, and the quiet household trade-offs that decide whether Class 9 is “possible” this year. Higher education, meanwhile, is being redesigned to look more flexible on paper, but the lived test is still brutally old-fashioned: Does the degree convert into work, or does it simply convert certainty into waiting? And above it all is the outward pull—students treating overseas study less as a postcard and more as an insurance policy, a bet on predictability when they aren’t convinced the domestic system will deliver it on schedule. Here, we read the Economic Survey as a map of where the system leaks and ask what this Budget will do: Patch the leaks, or just repaint the pipes.

Government schools win in number, private schools dominate in enrolment

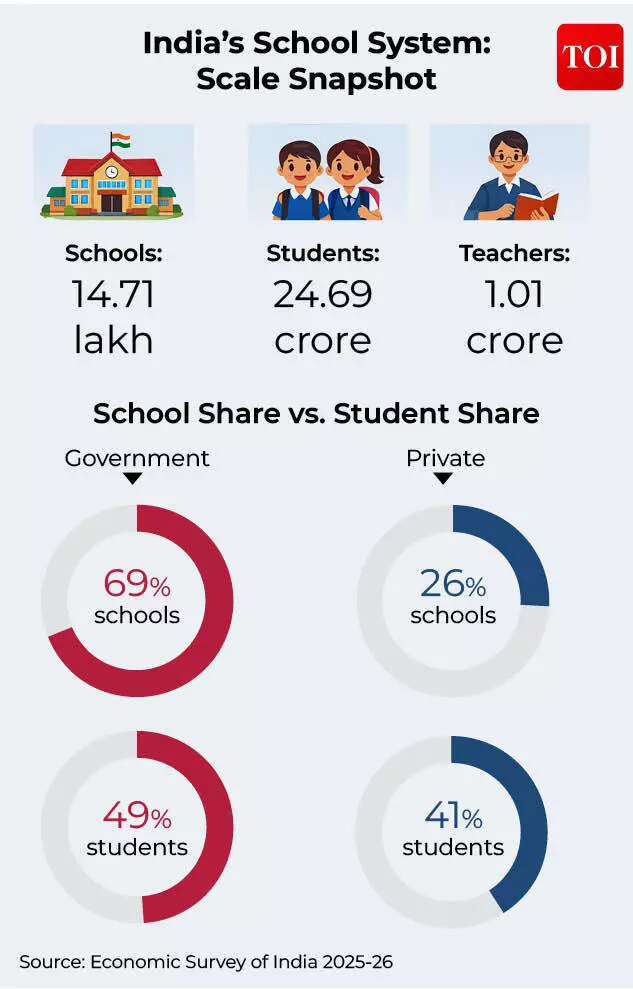

India’s school system is often discussed in abstractions—“enrolment”, “coverage”, “outcomes”—until you read the scale in one breath. The Economic Survey 2025–26 puts it plainly: 24.69 crore students, 14.71 lakh schools, and over 1.01 crore teachers (UDISE+ 2024–25).At this size, policy becomes an exercise in logistics before it becomes an argument about pedagogy. Then comes a second fact that’s less about volume and more about behaviour. Government schools form 69% of all schools and enrol nearly half of all students; private schools are 26% of the total but carry 41% of total enrolment (2023–24).

India’s School System

You don’t need to moralise this split to understand what it signals: Where government is the default infrastructure, private becomes the purchased promise—sometimes of English, sometimes of discipline, sometimes simply of predictability.

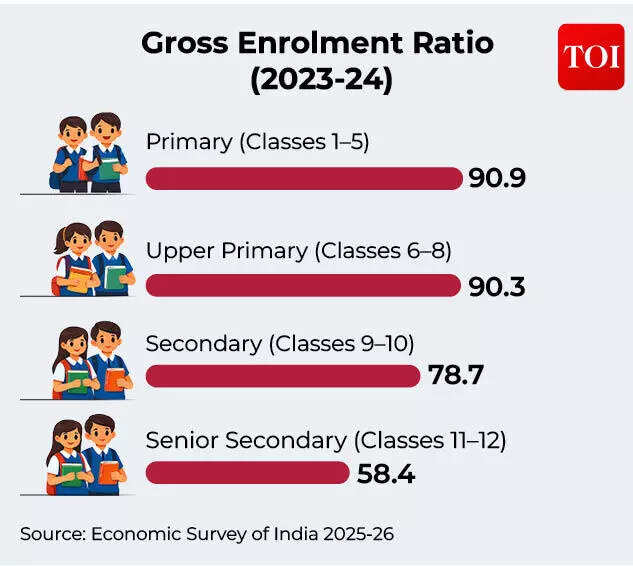

Enrolment stays strong in the early grades only

The participation curve looks steady—until it starts to taper. The survey tracks this through Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER), a measure of how many students are enrolled at a given level compared to the population in the official age group for that level.In 2023–24, GER is 90.9 at the primary level (Classes 1 to 5) and 90.3 at upper primary (6–8). That is the thick part of the pipeline: For most families, schooling still runs as the default. The slide begins at the secondary level. GER drops to 78.7 in Classes 9–10 and falls further to 58.4 in Classes 11–12. Put simply, far more children enter school than stay all the way through the last two years.

Gross Enrolment Ratio

A second cut of the same story, using NEP’s stage structure, reinforces the point. Here, “Secondary” is the entire 9–11 block (not just 9 and 10), so it captures the thinner participation in Classes 11 and 12 inside one figure. On this combined measure, GER at the secondary stage (9–11) is 68.5, compared to 95.4 at the preparatory stage (3–5) and 90.3 at the middle stage (6–8).The buckets are different, but the pattern is consistent: Access holds through the middle years, and becomes more conditional as schooling moves into adolescence and the senior-secondary stretch.

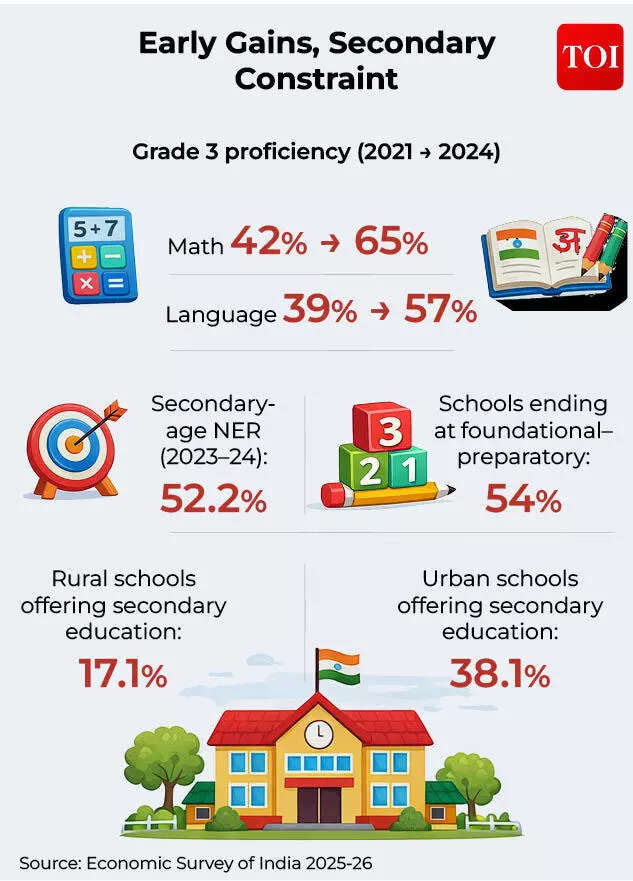

Early learning is improving, the real squeeze begins after Class 8

One of the few places where the survey offers a clean “before-and-after” on learning is the foundational stage. In Grade 3, proficiency levels rise over a visible timeline from 2021 to 2024: Mathematics improves from 42% to 65%, and Language from 39% to 57%.

Early Gains, Secondary Constraint

Whatever is driving it—stronger early-grade focus, sharper measurement, or plain old follow-through—the real takeaway is that the numbers are telling a story over time, not just posing for a single-year snapshot.But a rising trend doesn’t indicate a solved system. The other numbers make it clear that learning gains in the early grades do not automatically translate into smooth schooling in the later ones. The pressure point is the transition into secondary education—where the system starts to thin for reasons that are actually logistical. The survey notes that the secondary age-specific Net Enrolment Ratio (NER) is 52.2%—meaning only about half of the official-age cohort is enrolled at the secondary level.It also points to a supply-side constraint: 54% of schools offer only foundational–preparatory education, so continuing to secondary often requires shifting to another school. And the rural–urban gap sharpens the picture: In rural India, only 17.1% of schools provide secondary education, compared to 38.1% in urban areas.Read together, the findings land as an uncomfortable truth: Progress may show up in early-grade learning, but persistence in Class 9 still depends on geography. When secondary school means a longer commute, higher costs and more risk, families do the maths—and the pipeline thins.

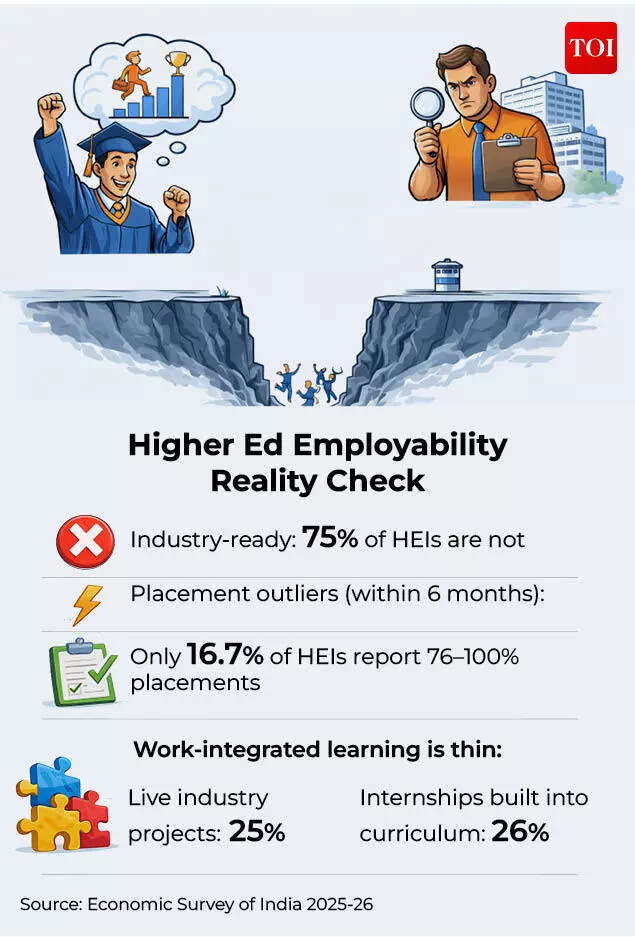

Flexible degrees, fragile bridges: HEIs still struggle with employability

Graduation is supposed to be the clean handover: You finish your credits, you collect your degree, you step into work. In India, that handover often comes with a waiting period—months in which families keep doing the arithmetic: How long before the degree starts paying for itself?

Higher Ed Employability Reality Check

A TeamLease EdTech report cited in the Economic Survey 2025–26 suggests the handover is uneven across campuses. It estimates that 75% of higher education institutions lack industry-readiness. The placement picture, in the same report, is not uniformly bleak or rosy—it is sharply lopsided. Only 16.7% of HEIs are reported to achieve 76–100% placements within six months. The ‘within six months’ detail is not just a metric. It is where uncertainty is lived as a clock that keeps moving, while the household absorbs the cost of delay. The more revealing constraint sits upstream, inside the degree itself. Only 25% of HEIs reportedly use live industry projects, and only 26% integrate internships into education. That is where the mismatch is manufactured. Students are asked to be “job-ready” at the exit gate, after years spent in programmes that too often treat industry exposure as optional. The risk, in effect, is shifted away from institutions and onto families—who pay first, wait next, and are then told the outcome is a matter of personal employability.

Study-abroad boom is outpacing its domestic pull

A decade ago, studying overseas was a big decision taken by a smaller slice of families. Now it is a corridor with scale. The Economic Survey 2025–26 captures that shift bluntly: Indian students abroad rise from 6.85 lakh in 2016 to over 18 lakh in 2025. In 2024, the imbalance is stark enough to read like a verdict without anyone writing one: for every one international student coming to India, 28 Indians went out. Here, the cost is not a footnote. It is the story’s shadow figure: Outward remittances under “studies abroad” are put at USD 3.4 billion in FY24.The issue here isn’t aspiration. It’s how aspiration is being organised and who profits from organising it. When outbound mobility reaches that scale, it ceases to be a simple story of individual choice. It becomes a structural response to domestic unpredictability: families hedge against an uneven system by purchasing certainty elsewhere, to the extent they can.The survey’s caution note is essentially an admission of how markets behave under pressure. A high-demand corridor invites cost inflation and aggressive commercialisation, pushing access toward those who can pay, while encouraging over-borrowing—of money, and of imported institutional templates—with regulatory spillovers following behind. Simply put, once anxiety is routinised, it becomes a business model. The family is made to carry the risk—first through fees and debt, then through the quiet uncertainty of whether the purchased pathway will deliver what the domestic one could not.

The education questions the Budget must answer

A sober reading of the Economic Survey 2025–26 doesn’t ask for applause. It asks for accountability. It points to a system where “choice” often hides compulsion. Families pay extra for predictability. Adolescents slip out when the next grade becomes farther, costlier, and riskier. Higher education is modernising pathways on paper. But too often, the degree-to-job bridge remains shaky. And the outward student tide looks less like wanderlust and more like a hedge against uncertainty at home.The Budget can answer this in two ways. It can add more layers—schemes, portals, slogans. Or it can repair the weak joints. It can fund the secondary transition. It can build work-linked learning into degrees. It can strengthen public capacity so certainty is not something households have to buy. That is the real choice. Patch the leaks, or repaint the pipes.