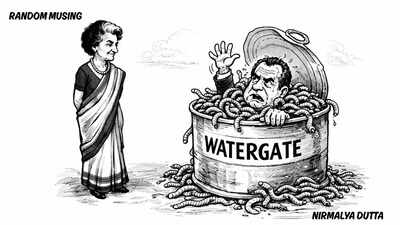

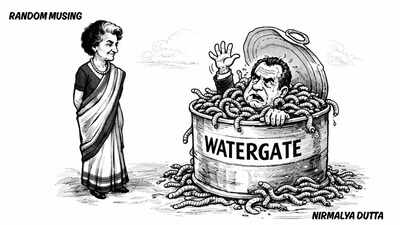

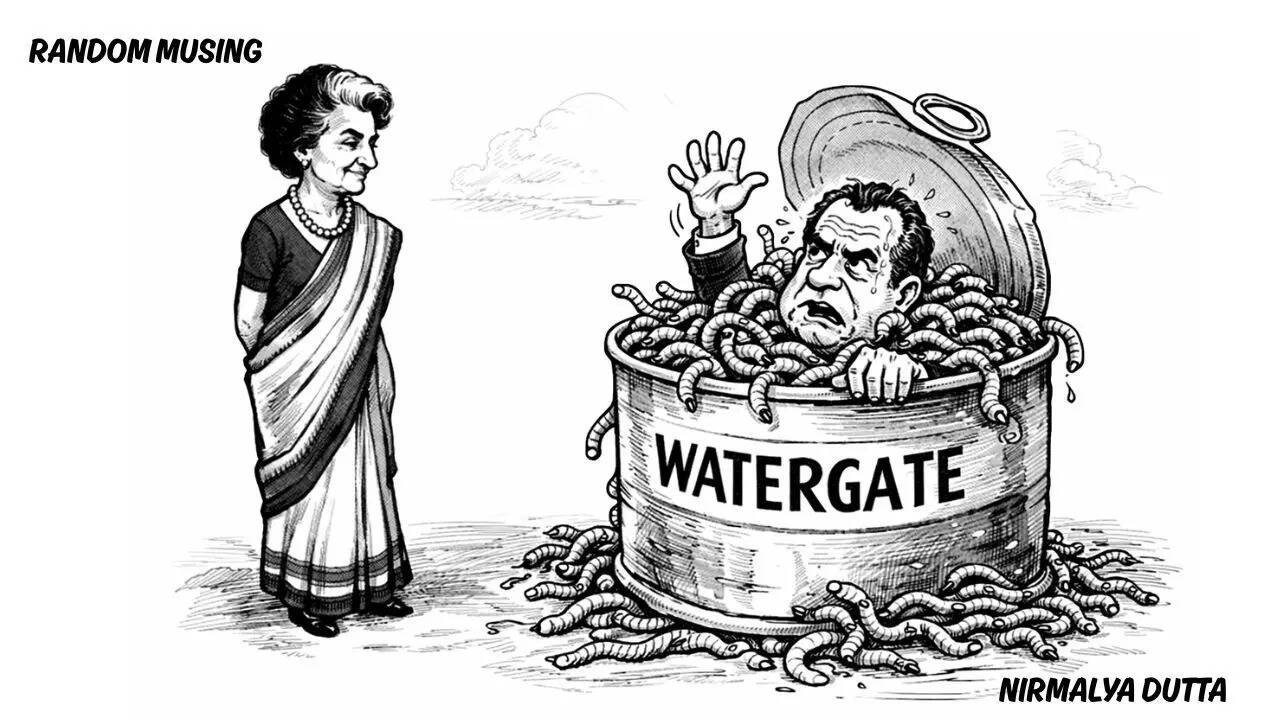

In The Whisky Priest, perhaps the best Yes, Minister episode — an assertion that is arduously dangerous, because picking the greatest Yes, Minister episode is like picking the greatest Beatles song — Sir Humphrey Appleby is aghast to learn that Jim Hacker is so bothered about Italian Red terrorists getting access to British weapons that he intends to broach the topic with the Prime Minister.Before explaining to Bernard Woolley, Jim Hacker’s private secretary, the importance of being a moral vacuum, Sir Humphrey insists they must stop the minister from informing the Prime Minister.When Bernard asks why, Sir Humphrey explains: “Because once the Prime Minister knows, there will have to be an enquiry, like Watergate. The investigation of a trivial break-in led to one ghastly revelation after another and finally the downfall of a president. The golden rule is don’t lift lids off cans of worms. Everything is connected to everything else.”

And boy, was he right.To this day, every time we shine a light on a Watergate, we discover a new can of worms.But first, for those joining us right now: what was the Watergate scandal?In simple terms, it is the journalist’s pipedream — that one’s reporting might lead to the destruction of a sitting government.For those without such ambitions, here’s the 4-1-1. In 1972, during a US presidential election campaign, a group of men were caught breaking into the Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington. They were there to steal documents and plant listening devices. That was just the first worm. It soon emerged that the burglars were linked to Nixon (the sitting president) who was the one with his finger on the fishing rod. What followed was the slow lifting of a very crowded lid: illegal wiretaps, campaign sabotage, hush money, cover-ups, and finally resignation. The suffix gate would henceforth be stapled onto every scandal, whether it made sense or not — Radiagate, Sand Papergate, Soan Papdigate — a linguistic tribute to bureaucratic wrongdoing.

The latest worm

At the height of Watergate, Nixon — and his prosecutors — decided that seven pages of sworn testimony were simply too dangerous to reveal, even to a full grand jury. Nixon warned his interrogator: “I would strongly urge the special prosecutor: Don’t open that can of worms.” And, remarkably, the prosecutors agreed.Which raises the obvious question. Why would men willing to prosecute a president over mafia links, illegal wiretaps and constitutional abuse quietly agree to bury seven pages of testimony?The answers range from Cold War sensitivities to fears of derailing détente. But the simplest explanation is also the most damning: it would have destroyed public confidence in the American state.Those seven pages revealed that for all his villainy, racism and misogyny — often directed at Prime Minister Indira Gandhi — Nixon did possess a peculiar sense of institutional loyalty. He believed some secrets were too destabilising even to expose in the name of justice.They also revealed that the American “deep state”, long imagined by critics and conspiracy theorists, existed in all its bureaucratic glory. And that the United States was hell-bent on helping Pakistan during the Bangladesh Liberation War — to the point of privately assuring China that Washington would back it if Beijing chose to attack India.This was not rogue chatter. Nixon insisted it was his decision, not Kissinger’s.

Nixon, the moral vacuum — selectively applied

Nixon was never known for his affection for the armed forces. On tape, he dismissed them as “greedy bastards” who wanted “more officers’ clubs and more men to shine their shoes.” Yet when prosecutors stumbled upon evidence that the military had been spying on his own civilian government, Nixon shut the door hard.On tape, Nixon was brutally candid about the men in uniform. “Goddamn it, the military — they’re a bunch of greedy bastards,” he complained. “They want more officers’ clubs and more men to shine their shoes. The sons of bitches are not interested in this country.” It is one of Watergate’s many ironies that a president who privately despised his generals still chose to protect them from public disgrace — not out of affection, but because exposing them would have torn a hole in the already fraying fabric of American authority. He warned that exposing this would “do irreparable harm” to the armed forces. Rather than drag intelligence agencies and military leadership into public disgrace — at a time when Vietnam had already made them deeply unpopular — Nixon chose resignation.Nixon’s distrust did not stop at the Pentagon. At one point, as Henry Kissinger walked out of a meeting, Nixon quipped: “There goes Henry … to call The Washington Post.” Even in a White House drowning in leaks, Kissinger — the architect of secrecy — was apparently suspected of briefing the press.In other words, Nixon would sacrifice himself before sacrificing the system. Not because he loved democracy, but because he feared what might replace it.

The war everyone talked over

The 1971 war was triggered not by territorial ambition but by a humanitarian and strategic crisis unfolding in East Pakistan. After Pakistan’s military launched a brutal crackdown following the 1970 election verdict, millions of Bengali civilians fled into India, creating an unsustainable refugee burden and a direct security challenge. New Delhi initially sought international pressure on Islamabad, but with the US and China backing Pakistan, India signed a treaty of peace, friendship and cooperation with the Soviet Union in August 1971 to secure strategic cover before turning to military action, only after Pakistan’s pre-emptive air strikes on December 3.The conflict in the east ended in just 13 days. Indian forces, alongside the Mukti Bahini, secured the surrender of Pakistan’s Eastern Command in Dhaka and midwifed the creation of Bangladesh — an outcome that reshaped South Asia’s strategic balance.Everyone else was busy role-playing the Cold War. India, inconveniently, finished the war before most others got their bearings.

Why China didn’t move

Of course, China never intervened. Several reasons explain this restraint. Beijing was still emerging from the wreckage of the Cultural Revolution, which had weakened institutions, disrupted command structures and encouraged caution rather than adventurism. Any move against India also risked entangling China in a wider confrontation with the Soviet Union. Crucially, the August 1971 Indo-Soviet Treaty signalled to Beijing that any move against India risked drawing in Moscow, sharply raising the cost of intervention.India, meanwhile, was no longer India of 1962.Its military had been reorganised, Himalayan defences strengthened, and political resolve made unmistakably clear. Most importantly, New Delhi moved with extraordinary speed — launching coordinated air, land and naval operations within hours of Pakistan’s strikes, securing air superiority in the east within days, cutting off reinforcements through naval blockades, and driving rapidly towards Dhaka.By the time the great powers finished calibrating escalation ladders, the war was effectively over.

The deeper state beneath the deep state

The seven pages also lift the lid on a more unsettling truth. The president was not the only one spying. The Joint Chiefs of Staff were spying on him. An enlisted man, Chuck Radford, became a human USB drive, rifling through briefcases, wastebaskets and burn bags, ferrying secrets from civilian leadership to uniformed commanders.Radford was no master spy. He was, by most accounts, an easygoing, sharply observant young Navy yeoman with an extraordinary memory — a man who copied documents, memorised what he could not copy, and rifled through briefcases and burn bags with monk-like discipline. He even accompanied Kissinger on secret trips to Pakistan, quietly noting how the secretary of state pretended to fall ill, slipped away, and reappeared in Beijing. In another era, Radford would have been a footnote. In Nixon’s America, he became a constitutional problem.Congress eventually shrugged. Admirals retired with full honours. Everyone agreed it was best to keep very quiet about it all. Watergate, it turns out, was not the scandal Nixon feared most. It was the decoy. The real danger lay in exposing how casually power spied on itself — and how easily it justified doing so.Nixon himself seemed to understand this best when he admitted: “I created this whole situation, this lesion. It’s just unbelievable.”At one point, Nixon even wondered aloud whether he should wiretap General Haig — a suggestion so perfectly Nixonian it barely registered as satire.As Sir Humphrey might have put it, once you lift the lid, you never know where it stops. Or, as an Indian politician once summarised the entire affair far more efficiently: Sab mile huey hain, jee.Everything is connected to everything else. Lenin said it first. Sir Humphrey reminded us of that. And Watergate keeps proving it — one worm at a time