Parliament will begin a special discussion in the Lok Sabha on Monday to commemorate 150 years of Vande Mataram, a song that remains one of the most debated symbols of India’s freedom struggle.Prime Minister Narendra Modi will open the debate, with defence minister Rajnath Singh scheduled to conclude it. The BJP has been given three hours in the Lok Sabha, the total debate will span nearly ten hours. The Rajya Sabha will hold its discussion the next day, to be opened by Union home minister Amit Shah.The commemoration is not merely ceremonial. It arrives amid renewed political sparring over the song’s historical evolution, religious imagery, and the choices made by India’s pre-independence national leadership. What began as a patriotic hymn in a Bengali novel is once again a focal point of fierce political messaging, competing historical narratives, and questions about national identity.This explainer traces the 150-year journey of Vande Mataram—from its birth in Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay’s writing to its role in nationalism, the Congress’s 1937 decision to officially use only its first two stanzas, and its recognition in the Constituent Assembly as having “equal honour and status” with the National Anthem.

Why it’s in the news now

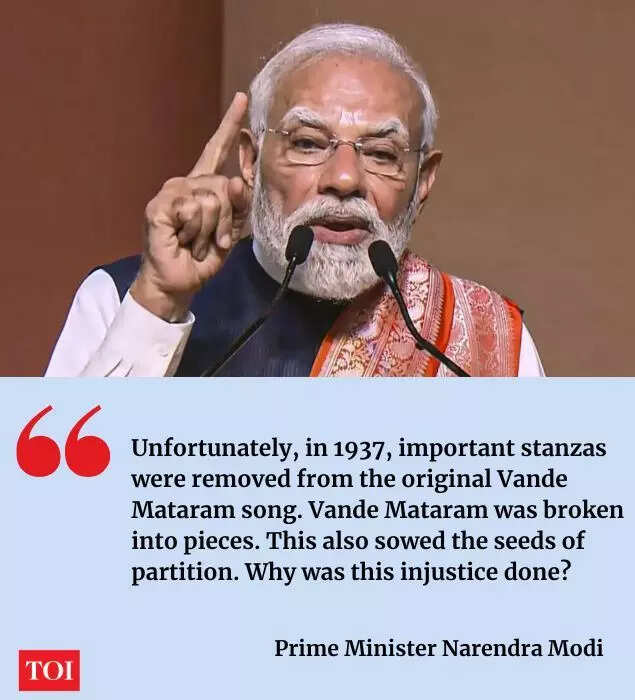

The upcoming debate is part of a special parliamentary focus on the legacy of Vande Mataram. But the political temperature was raised last month, during the commemoration event of 150 years of the national song, when Prime Minister Modi accused the Congress of having “removed important stanzas” from the original song during its 1937 Faizabad session, claiming this decision “sowed the seeds of partition.”According to the Prime Minister, the Congress’s move amounted to breaking the national song into pieces—an act that abandoned its original spirit and undermined unity. He has framed the issue within his broader narrative of ‘Viksit Bharat’, tying cultural heritage to national development.

The Congress hit back immediately. Citing The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (Vol66, p46), the party argued that the 1937 decision was not an act of division, but a sensitive accommodation recommended by a Working Committee that included Mahatama Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Subhas Chandra Bose, Rajendra Prasad, Abul Kalam Azad, Sarojini Naidu, and other iconic leaders. The CWC noted that the first two stanzas were already the only widely sung and nationally recognised part, while the remaining contained religious imagery that some citizens objected to.The Congress also emphasised that the decision drew from the advice of Rabindranath Tagore, who had himself sung Vande Mataram at the 1896 Congress session.In its rebuttal, the party accused the prime minister of attacking the legacy of India’s freedom movement while avoiding present-day issues such as unemployment, inequality, and foreign policy challenges.This political exchange has made the upcoming parliamentary debate all the more charged.

Origins of Bande Mataram (1870s–1880s)

The PIB’s historical account helps clarify the origins of the song. According to Sri Aurobindo’s writing in the English daily Bande Mataram (16 April 1907), Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay composed the song around 1875. It was published more widely when Bankim’s novel Anandamath began serialization in the Bengali magazine Bangadarshan in March–April 1881.Song’s literary context: AnandamathAnandamath is built around a group of ascetic warriors, the Santanas, who dedicate themselves to freeing the motherland from oppression. Their devotion is entirely to Bharat Mata, envisioned not as a religious deity but as a personified motherland.In the temple of the Santanas stand three images of the Mother:

- The Mother that was – glorious and mighty

- The Mother that is – suffering and oppressed

- The Mother that will be – restored to strength and glory

For Aurobindo, the hymn embodied the essence of “the religion of patriotism.”Many later critics, however, would argue that the imagery—particularly in the later stanzas—draws from Hindu goddess symbolism that may not be inclusive of all communities.

From song to slogan: Birth of a nationalist cry (1900–1910)

By the early 20th century, Vande Mataram had escaped its literary origins and become one of the most electrifying symbols of Indian nationalism.Swadeshi and anti-partition movementAfter Lord Curzon’s 1905 partition of Bengal, the song became the rallying cry for:

- Boycott movements

- Protest marches

- Newspapers and political groups carrying its name

In 1906, at Barisal, more than 10,000 Hindus and Muslims together marched shouting Vande Mataram—a testament to its early cross-communal appeal.Figures who popularised it included:

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Bipin Chandra Pal

- Sri Aurobindo

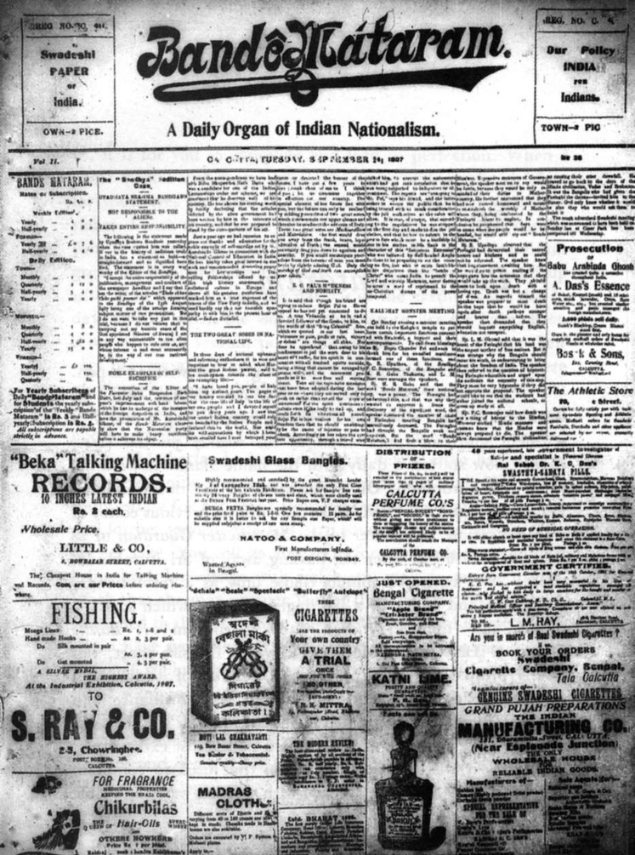

Aurobindo’s writings in Bande Mataram (the newspaper) turned the phrase into a political and spiritual exhortation for self-rule.

British repressionAlarmed by its galvanising effect, the colonial government tried repeatedly to suppress it through:

- Fines for students

- Police lathi-charges

- Bans on marches

- Threats of expulsion from schools and colleges

From Bengal to Bombay Presidency, chanting Vande Mataram became synonymous with nationalist defiance.In 1907, Madam Bhikaji Cama unfurled the first tricolour abroad—in Stuttgart—with the words Vande Mataram emblazoned across it.

The song and the Indian National Congress

The Congress adopted Vande Mataram not just culturally, but ceremonially.1896 —First Congress rendition: At the Calcutta session, Rabindranath Tagore sang the song, giving it national prominence.1905 — Nationwide adoption: At the Varanasi session, the Congress formally adopted Vande Mataram for all-India occasions. This was during the peak of the Swadeshi struggle, when the song had become the soundtrack of political awakening.

1937 CWC decision: Were the stanzas removed?

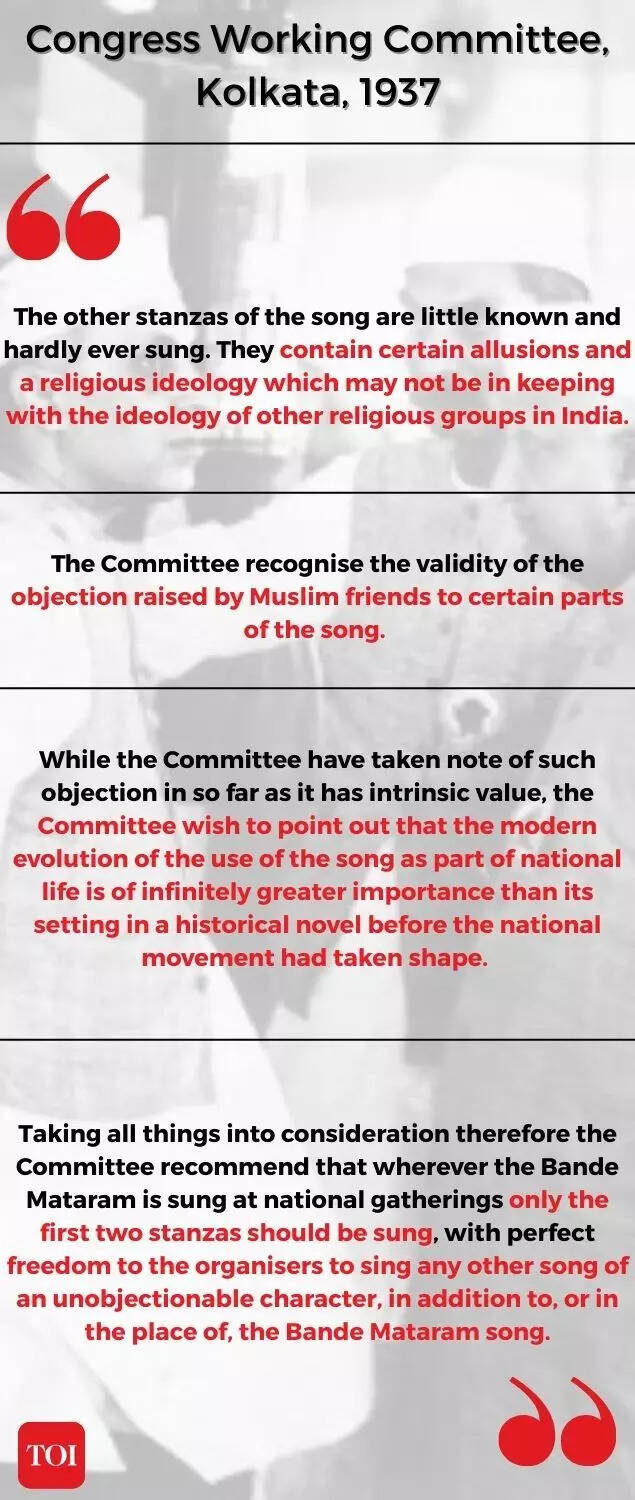

Yes.By the 1930s, debates around the song’s religious imagery had become politically relevant. India’s nationalist leadership wanted to keep the movement inclusive, and Muslim leaders raised objections to certain stanzas that invoked Hindu goddesses.

Did it ‘sow seeds of partition’?

No.The CWC’s decision was more inclusive than divisive in nature.The eventual decision to restrict Vande Mataram to its first two stanzas drew directly from this history of selective popular usage. As the Committee noted, only the opening verses — celebrating the land’s beauty and abundance in gentle, inclusive imagery — had organically acquired national significance over the decades. The remaining stanzas were scarcely known, rarely sung, and contained religious allusions and ideological references that many felt were inconsistent with the beliefs of other communities. The CWC explicitly acknowledged the “validity of the objections raised by Muslim friends” to those portions. While emphasising that the song’s modern, unifying role in national life mattered far more than its origins in a historical novel, the committee concluded that only the first two stanzas should be sung at national gatherings. This, they argued, preserved the unifying spirit the song had come to embody while avoiding elements that could alienate sections of India’s diverse society.What the 1937 CWC actually saidThe CWC’s statement, issued between October 26–November 1 in Kolkata, recorded:

- The first two stanzas had become widely used and carried no controversial imagery.

- The remaining stanzas contained “allusions and a religious ideology” inconsistent with the beliefs of other religious groups.

- Only the first two stanzas should be sung at national gatherings.

- Organisers were free to choose additional songs if they wished.

The committee explicitly said that the modern national use of the first two stanzas was more important than the song’s original placement in a religiously infused novel.Tagore had long argued that when a cultural symbol is used nationally, it must not exclude or alienate. His views shaped the committee’s decision and remain central to the Congress’s defence today.

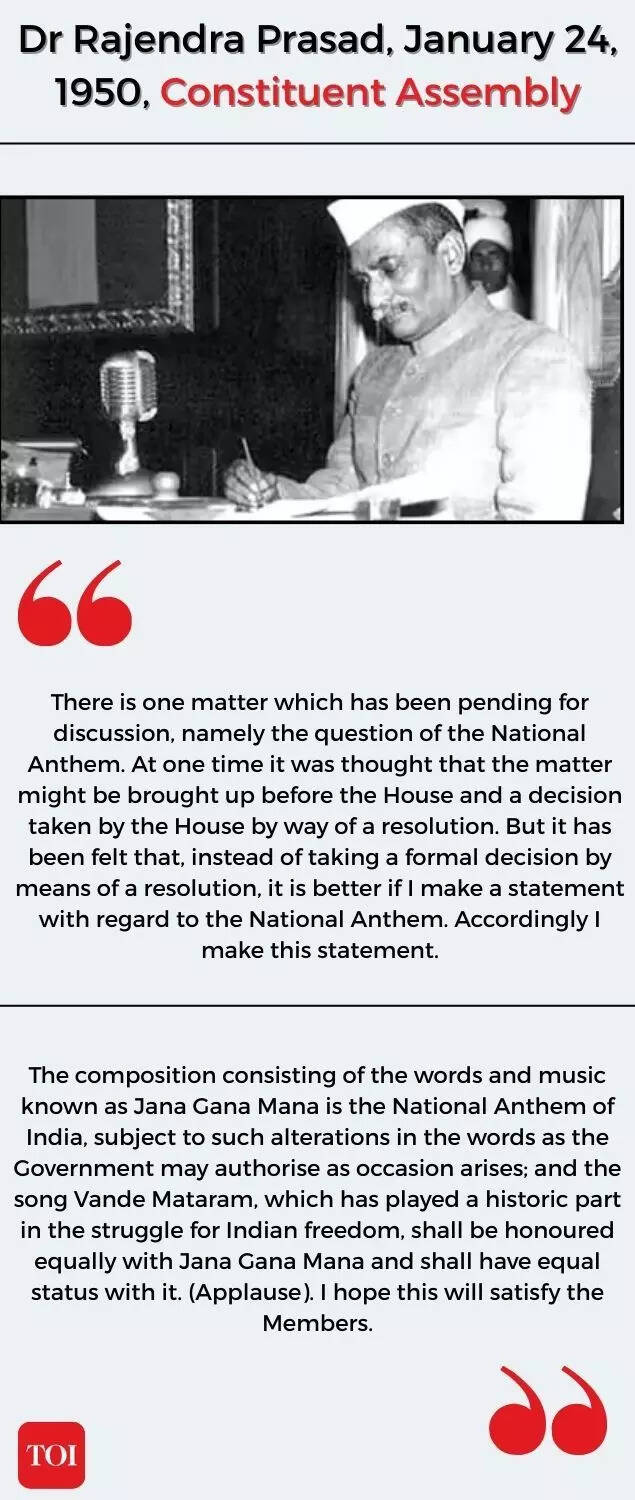

Constituent assembly: Equal honour, equal status (1950)When the Constituent Assembly met to choose India’s national symbols, there was no dispute between Jana Gana Mana and Vande Mataram.In his statement on January 24, 1950, DrRajendra Prasad, President of the Assembly, declared:Jana Gana Mana would be the national anthem.Vande Mataram, because of its historic role, would be honoured equally and accorded equal status.There was applause; no member raised objections.This dual recognition was meant to preserve both inclusivity and historical memory: the anthem would represent national unity, while Vande Mataram’s legacy would be canonised as part of India’s freedom story.

The debate today

Why is the BJP reviving the issue?For the ruling party, Vande Mataram is a civilizational invocation that predates partisan politics. The BJP frames the 1937 Congress decision as overly accommodative, even compromising, and often ties this critique to a larger argument about “appeasement.”In the government’s view, celebrating 150 years of the song is part of a project to reaffirm cultural pride and national self-confidence.Why is the Congress defensive?The Congress insists it is the party that first elevated the song, sang it at historic moments, and fought the British under its banner. It argues that:

- The 1937 decision was guided by inclusivity, not division.

- The BJP is weaponising history to distract from contemporary governance failures.

- Tagore and the freedom movement need protecting from political revisionism.

What Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind has to say

The Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, led by Maulana Mahmood Madani, has taken a clear and consistent position on the Vande Mataram debate: it accepts the first two stanzas as historically validated for national use but firmly rejects the remaining verses on theological grounds. Madani argued that the full composition contains imagery — particularly the depiction of the motherland as the goddess Durga — that conflicts with Islamic monotheism, making it impermissible for Muslims to recite.“He stated that Vande Mataram in its complete form is rooted in shirkiya aqaaid (polytheistic beliefs). Particularly, in the remaining four stanzas, the motherland is depicted as the goddess Durga and addressed with words of worship — concepts that clearly conflict with the Islamic belief in the oneness of God. ‘Muslims believe in one God and worship Him alone,’ Maulana Madani said. ‘Therefore, singing verses that ascribe divinity to anyone other than Allah goes against our faith and conscience,'” a statement by Jamiat said.