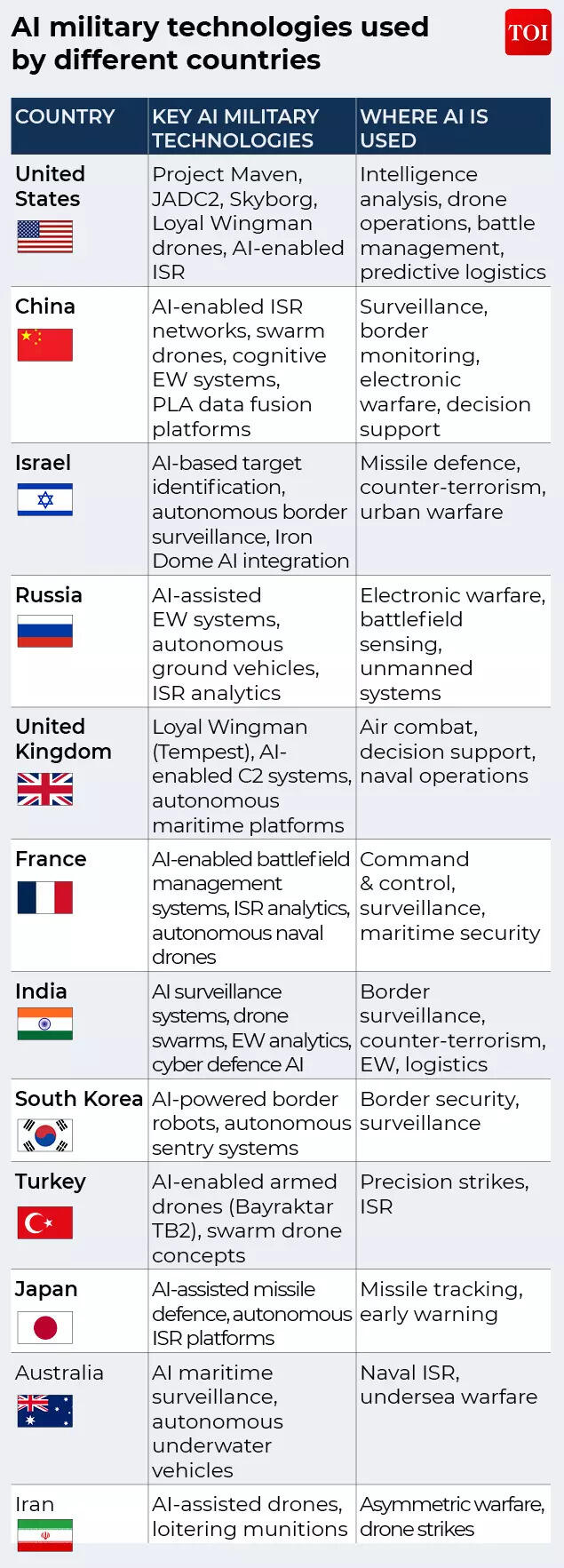

Modern wars are no longer decided only by tanks rolling across borders or fighter jets dominating the skies. Increasingly, outcomes are shaped long before the first missile is launched — in data centres analysing satellite feeds, in cyber units probing adversary networks, and in electronic warfare suites quietly blinding sensors and scrambling communications. For India, which faces a complex security environment ranging from cross-border terrorism to a contested continental and maritime neighbourhood, the push to integrate artificial intelligence (AI), cyber warfare and electronic warfare (EW) into its military architecture has become not just a matter of modernisation but of strategic necessity.Over the past decade, India’s armed forces have moved steadily — if unevenly — towards a technology-centric doctrine. What distinguishes the current phase is the scale and seriousness of this shift. AI-enabled surveillance systems now watch borders once manned by thousands of soldiers. Cyber units prepare for conflicts that may never involve a single shot being fired. Electronic warfare platforms are increasingly central to air, land and naval operations. Together, these capabilities represent a fundamental rethinking of how India plans to deter, fight and win future wars.

How AI shaped Operation Sindoor’s planning and executionArtificial intelligence played a central role in Operation Sindoor, particularly in the intelligence assessment and planning stages that preceded the pre-dawn missile strikes on nine terror targets in Pakistan and Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir. According to senior Army officials, AI-enabled systems were used extensively to generate a common operational picture, conduct intelligence analysis, assess threats and support predictive modelling for long-range strikes.

.

The Army employed AI tools for real-time multi-sensor and multi-source data fusion, drawing inputs from satellite imagery, aerial surveillance platforms, electronic intercepts and historical intelligence databases. This enabled planners to identify patterns of militant activity, validate the credibility of targets and narrow down locations that met both operational and political thresholds. In all, 23 task-specific AI applications were deployed to process data and inputs during the operation, officials said.AI-driven analytics were also used to prioritise targets, factoring in infrastructure significance, occupancy patterns, proximity to civilian areas and potential collateral damage. Multiple simulations and scenario models helped planners shortlist nine high-value targets with greater precision and confidence.During execution, AI-supported real-time situational awareness allowed commanders to track strike progress, assess outcomes and maintain coordination across units. Predictive modelling and AI-enabled weather forecasting tools further aided artillery units and long-range vectors, enabling precise timing and targeting under dynamic conditions.Lieutenant General Rajiv Kumar Sahni, Director General of Electronics and Mechanical Engineers (EME), said indigenous AI systems such as the Electronic Intelligence Collation and Analysis System (ECAS) were upgraded in real time to identify and prioritise critical threats, helping the Army achieve what he described as “strategic dominance”. Another system, Trinetra, integrated with Project Sanjay, provided a unified operational picture that improved coordination, situational awareness and decision superiority.Operation Sindoor, Sahni noted, reflected India’s growing technological self-reliance and demonstrated how scientific capability directly strengthens national defence preparedness. The operation illustrated how AI-driven intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance can shorten decision cycles while improving accuracy, while also reducing dependence on manual analysis and foreign technology at critical moments.AI on the battlefield: Augmentation, not autonomyArtificial intelligence has emerged as the backbone of this transformation. Contrary to popular imagery of fully autonomous killer robots, India’s military use of AI is largely focused on augmentation — enhancing human decision-making rather than replacing it.

.

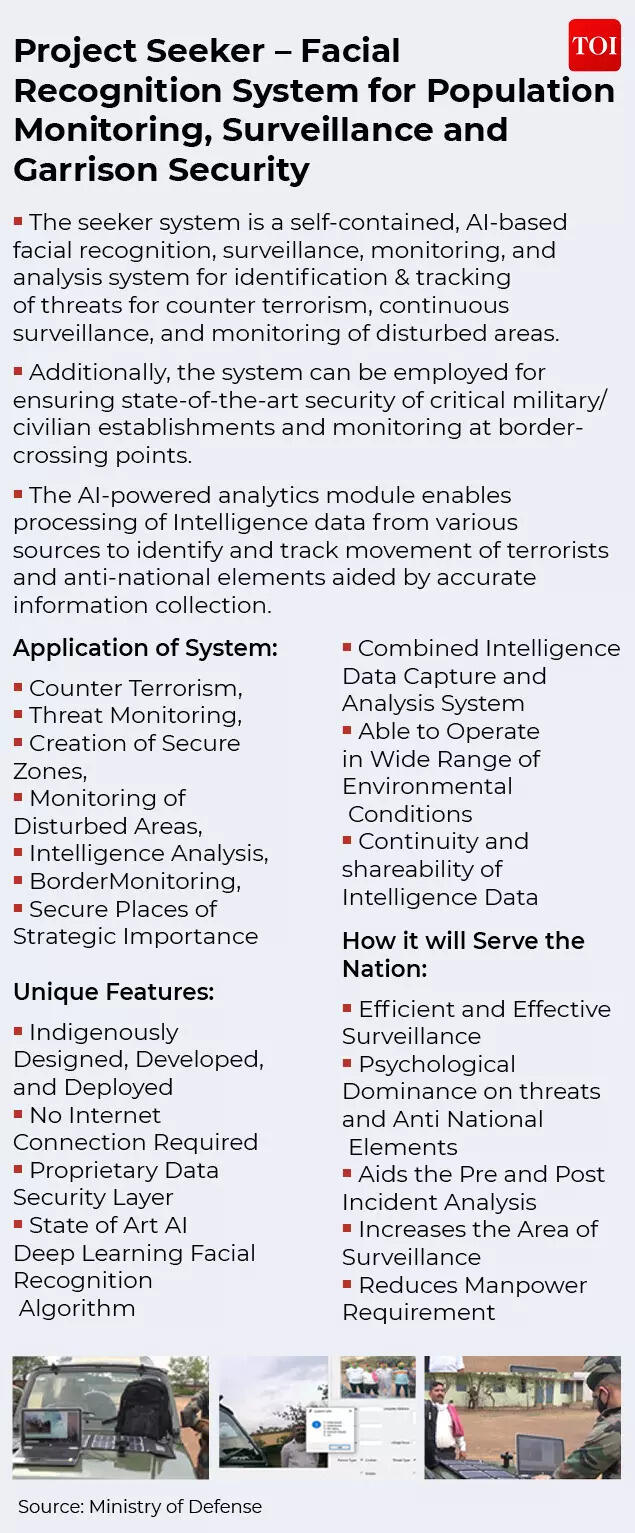

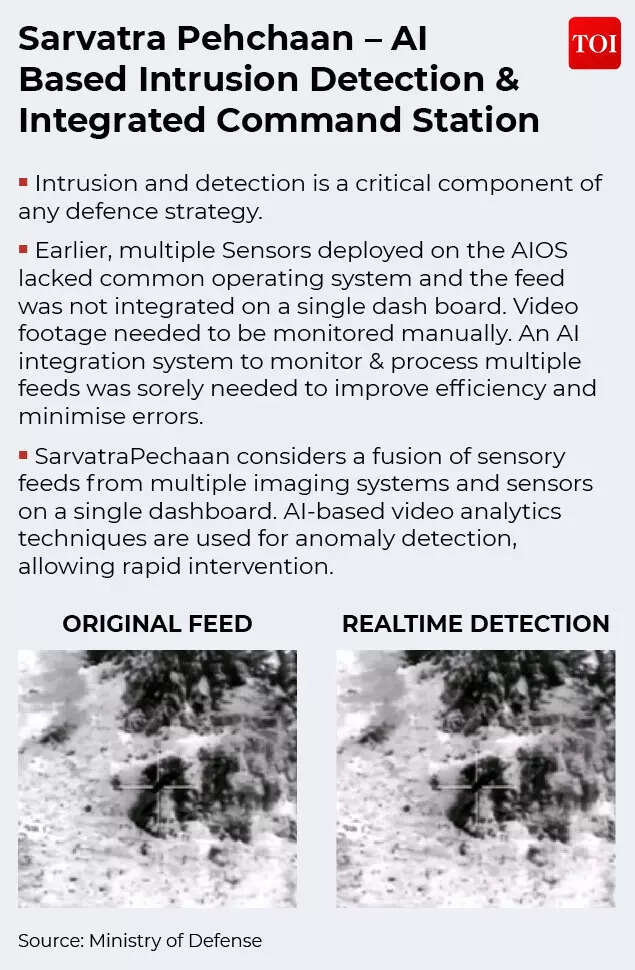

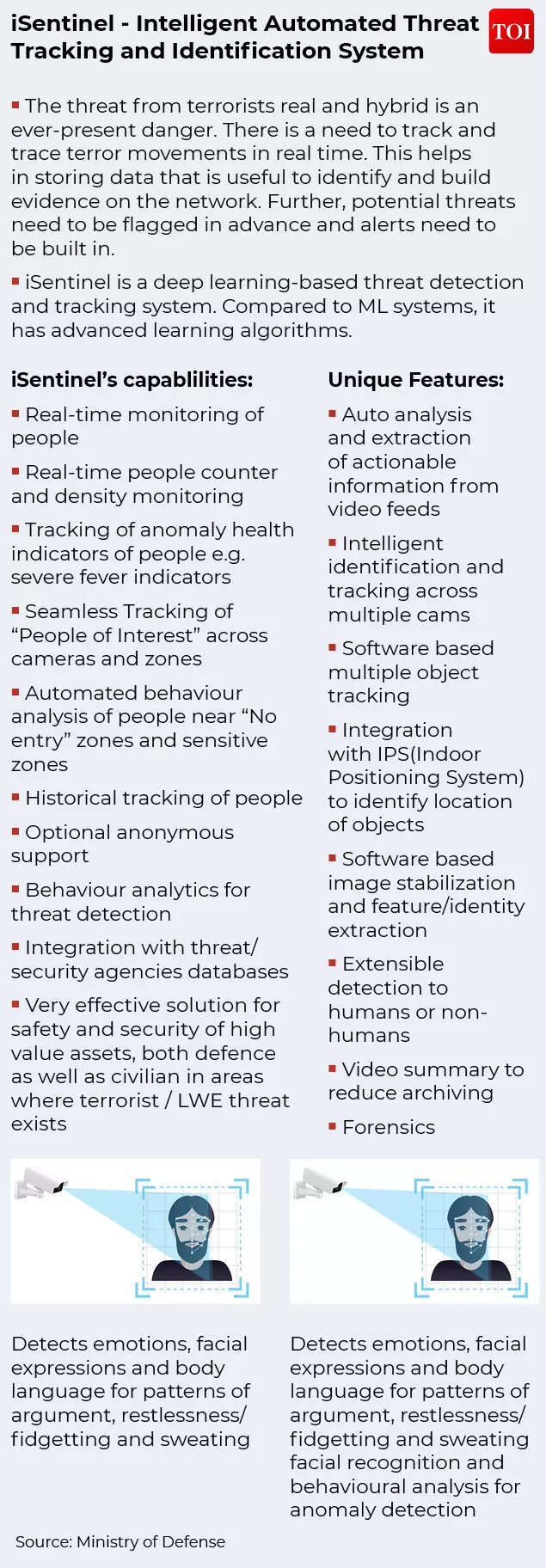

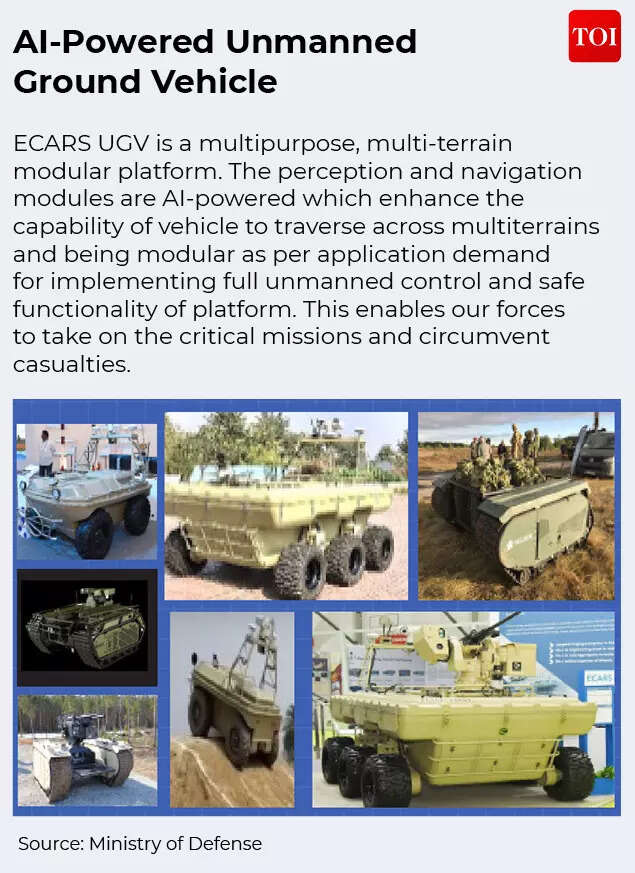

Across the Army, Navy and Air Force, AI is being deployed to tackle one persistent challenge: information overload. Modern sensors generate vast quantities of data — from drones, radars, satellites, thermal imagers and electronic intercepts. Human analysts simply cannot process this deluge in real time. AI systems, trained to detect patterns and anomalies, now act as force multipliers.AI-enabled surveillance platforms deployed along the Line of Control (LoC) and Line of Actual Control (LAC) can automatically flag suspicious movement, classify objects and generate alerts, reducing dependence on continuous human monitoring. In counter-terrorism environments, facial recognition and behavioural analysis tools assist forces in tracking suspects across crowded urban spaces, though their use remains tightly controlled due to legal and ethical concerns.In the Air Force and Navy, AI is increasingly used for predictive maintenance — analysing vibration, temperature and performance data to forecast component failures before they occur. This improves fleet availability while reducing costs, a crucial advantage in a force that operates diverse and often ageing platforms.Drones and swarms: The democratisation of air powerIf AI provides the brain, drones provide the eyes — and increasingly, the sting. India’s experience with unmanned systems has expanded rapidly, moving from basic reconnaissance platforms to loitering munitions, armed drones and swarm concepts.What makes drones disruptive is not just their capability but their economics. Small, expendable platforms can perform missions once reserved for expensive aircraft or heavily defended ground patrols. In contested environments, numbers matter as much as sophistication.Swarm drones represent the logical next step. By networking multiple unmanned aerial vehicles through AI-driven coordination algorithms, swarms can saturate defences, confuse radar systems and attack targets from multiple vectors. Indian research institutions and military units have conducted trials demonstrating autonomous formation flying, collision avoidance and coordinated target search.

.

Unlike traditional air operations, swarms rely on distributed intelligence. There is no single point of failure. Even if several drones are neutralised, the swarm adapts and completes its mission. For defenders, this creates an asymmetry: expensive missiles and air defence systems are forced to engage low-cost targets.India’s drone doctrine increasingly views swarms as complementary to conventional air power rather than substitutes. They are tools for shaping the battlefield — degrading defences, gathering intelligence and creating openings — rather than delivering decisive blows on their own.Cyber and electronic warfare: Fighting in invisible domainsCyber and electronic warfare now form the invisible front lines of modern conflict, operating below the threshold of open war yet shaping outcomes long before kinetic force is applied. Often described as the fifth domain of warfare alongside land, sea, air and space, cyber operations are among the least visible — and most misunderstood — tools of military power.For India, the creation of the Defence Cyber Agency marked formal recognition that future conflicts will involve sustained cyber operations targeting military networks, logistics chains, command systems and, in some cases, civilian infrastructure that supports war efforts. Unlike traditional attacks, cyber operations can be conducted continuously, discreetly and with plausible deniability, complicating deterrence and response.

.

Modern military platforms are effectively networked computers. Aircraft, ships, missiles and radars depend on software-driven navigation, targeting and communications, creating vulnerabilities that adversaries seek to exploit through malware, supply-chain compromises and data exfiltration. India’s cyber posture therefore emphasises resilience — network segmentation, encryption, indigenous software development and regular red-team exercises aimed at limiting systemic failure. At the same time, offensive cyber capability is viewed as essential for disrupting adversary command and control during crises.

Electronic warfare operates in parallel, contesting the electromagnetic spectrum on which modern militaries rely. EW involves jamming, deception, interception and protection of electronic signals, from radar emissions to communication links. In high-intensity conflict, control of the spectrum often determines the tempo of battle. Platforms without effective EW suites remain vulnerable, regardless of their technological sophistication.Indian forces have accelerated the induction of indigenous EW systems, including radar warning receivers, jammers and decoy dispensers across air, land and naval platforms. Warships deploy EW suites capable of detecting and classifying emissions across wide maritime areas, while ground-based EW units support formations by disrupting adversary sensors and communications.

.

The growing integration of AI into cyber and EW systems marks a critical leap. Machine-learning algorithms can rapidly classify unfamiliar signals, adapt jamming techniques and separate genuine threats from background noise in real time. In contested environments where milliseconds matter, this speed increasingly determines survivability and operational success.Indigenous push and technological self-relianceOperation Sindoor marked a decisive moment in India’s long-running push for defence indigenisation, offering rare battlefield validation of systems developed under the Aatmanirbhar Bharat framework. Defence minister Rajnath Singh, addressing DRDO scientists and technical personnel after the operation, said the mission demonstrated that indigenous systems are now strengthening India’s operational readiness, rather than merely supplementing imported capabilities.“Self-reliance has become a national mindset,” Singh said, crediting DRDO’s technologies for being “effectively used on the battlefield” during Operation Sindoor. His remarks, made at a Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) function following the 77th Republic Day Parade, underscored a shift in how indigenisation is being measured — not by prototypes or trials alone, but by deployment under live operational conditions.

.

Senior defence officials involved in the operation said AI-enabled, home-grown analytical and decision-support systems played a critical role in intelligence fusion, threat prioritisation and mission planning. This, Singh noted, reflected a broader transformation of the defence sector driven by indigenous research, accelerated induction cycles and closer integration between the armed forces, DRDO and industry.The defence minister framed the technological race in stark terms. “In today’s times, especially on the battlefield, we must move forward with the theory of ‘survival of the fastest’ and not just ‘survival of the fittest’,” he said, warning that technologies considered cutting-edge today can become obsolete within a few years. The emphasis, he argued, must be on speed — in research, decision-making and deployment.A key structural weakness Singh highlighted was the time lag between research and induction. Calling for urgent reforms, he said the biggest performance metric for defence R&D should be “reducing the time between research to prototype, prototype to testing, and testing to deployment”, adding that timely induction into the armed forces must outweigh purely laboratory-based achievements. To bridge this gap, the government has pushed for co-development models in which industry partners are involved from the design stage itself, rather than brought in only at the production phase.The Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) 2020 prioritises the Buy (Indigenously Designed, Developed and Manufactured) category for capital procurement, while government-funded innovation schemes such as the Technology Development Fund (TDF) and iDEX have expanded sharply. Funding caps under TDF have been raised to Rs 50 crore per project, while iDEX Prime now allows grants of up to Rs 10 crore, signalling the state’s willingness to underwrite technological risk.

.

Singh was explicit that DRDO must move beyond a monopolistic R&D model. “Government support will only be meaningful when DRDO cooperates with the public sector, private industries, MSMEs, start-ups and academia,” he said, pointing to programmes such as the Light Combat Aircraft Tejas as evidence of what collaborative development can achieve. Similar models, he suggested, are now essential in emerging domains such as drones, electronic warfare systems, radars and AI-enabled platforms.The results are beginning to show in export figures. Defence exports, which stood at under Rs 1,000 crore in 2014, have climbed to around Rs 24,000 crore, with the government targeting Rs 50,000 crore by 2029–30. Singh urged DRDO to factor in export potential at the design stage itself, arguing that global markets not only recover costs but also enhance strategic credibility and partnerships.Operation Sindoor thus sits at the intersection of policy intent and operational outcome. It illustrated how indigenous technologies — once criticised for delays and limited scope — are now being absorbed into core military functions such as intelligence analysis, targeting and battlefield decision-making. More importantly, it reinforced the government’s argument that technological self-reliance is no longer just about reducing imports, but about preserving strategic autonomy and operational freedom in high-stakes conflicts.

.

The road ahead: Integration over innovationThe future of India’s military transformation will depend less on acquiring cutting-edge gadgets and more on integrating existing capabilities effectively. AI, cyber and EW are only as powerful as the doctrines, training and organisational cultures that employ them.Jointness — coordination among the Army, Navy and Air Force — is essential in multi-domain operations. Data-sharing protocols, common communication standards and integrated command structures will determine success more than individual platforms.India’s push for AI, cyber and electronic warfare dominance reflects a sober assessment of the future battlefield. Wars will increasingly be decided in invisible domains — through algorithms, signals and data — long before they are visible on television screens.Operations like Sindoor suggest that India is learning to fuse technology with doctrine, leveraging indigenous capabilities to achieve precision and restraint. The challenge ahead lies in scaling these successes, safeguarding ethical norms and staying ahead in a rapidly evolving technological contest.The next war India prepares for may never be declared formally. It may unfold quietly, in networks and spectra, before erupting — or being deterred altogether. In that reality, dominance will belong not just to those with the strongest weapons, but to those who master the invisible battles that shape modern warfare.