Across parts of rural Japan, a shift is underway that has little to do with dams or new pipelines. Instead, it is happening inside individual homes. In villages facing population decline and rising maintenance costs, some households are testing compact water systems that operate without a public supply. These units recycle water on site, turning everyday use into a closed loop. The change comes as national agencies warn that existing infrastructure is becoming harder to sustain, especially in remote areas with fewer residents to support it. Rather than extending networks ever further, attention is turning inward, toward self-contained solutions. What is emerging is not a dramatic overhaul but a practical response to a long-standing problem.

Japan’s water infrastructure is being rewritten from the inside

Japan’s water infrastructure was built for a larger, denser population. In many regions, that population no longer exists. Pipes still run for kilometres to service a handful of homes. Treatment plants require constant upkeep regardless of how many people remain connected.Local authorities have flagged the water supply as a growing burden. Repair costs rise while usage falls. In some areas, officials have begun to question whether maintaining full networks makes sense at all. This has opened the door to alternatives that would once have seemed temporary or niche.

Compact units allow homes to manage their own water

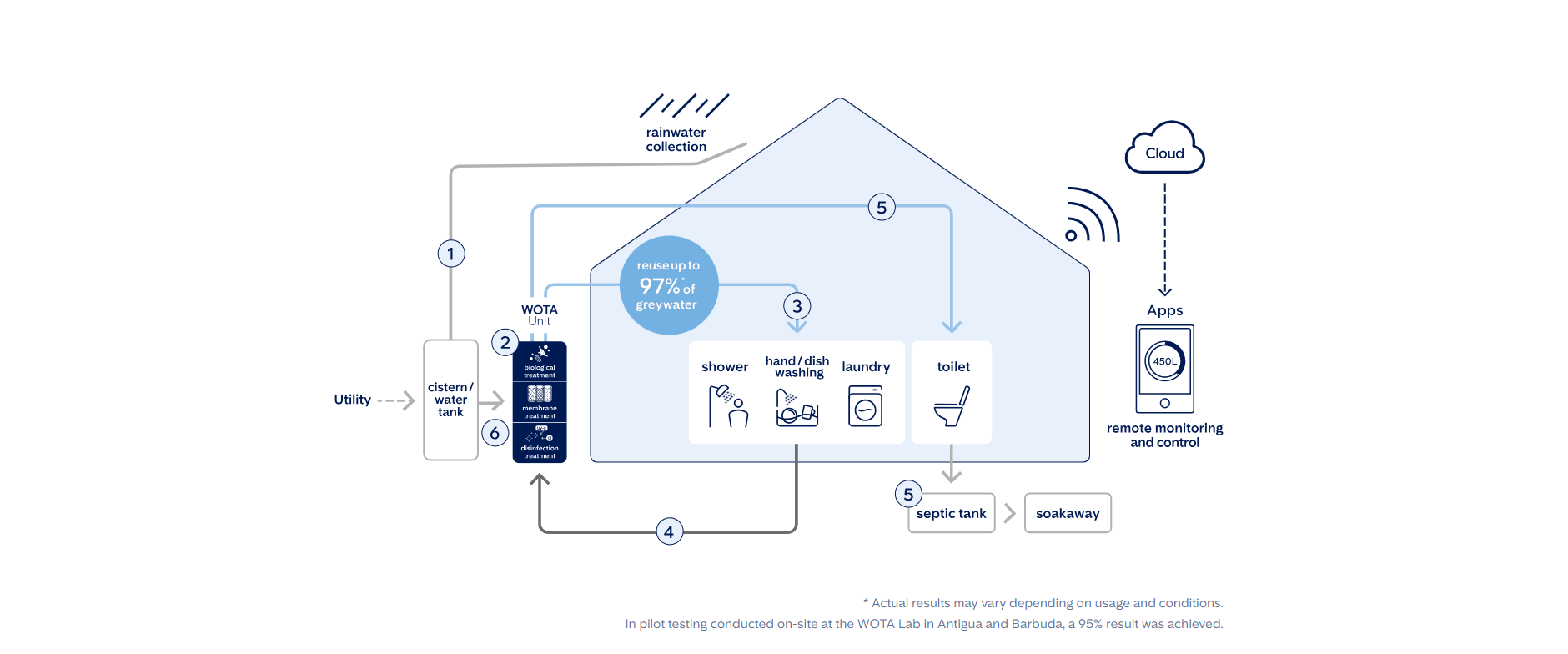

One of the systems now under evaluation is the WOTA BOX, developed by Tokyo-based firm WOTA Corp. Rather than connecting to municipal pipes, the unit operates as a standalone household water system. Installed inside the home, it captures water from showers, sinks, and washing machines, then treats and reuses it. Up to 97% of this greywater can be regenerated and circulated again for everyday domestic use.

WOTA BOX, developed by Tokyo-based firm (Image Source – WOTA)

Toilet waste is kept separate and sent to a standard septic tank. Drinking water is also handled independently. Any water lost during daily use is replaced with rainwater collected from the roof and filtered through the same system. Treatment relies on a combination of biological processing, fine membrane filtration, and disinfection using UV light and small amounts of chlorine. Sensors and automated controls manage the process quietly in the background.The result is a household that can function without access to a public water supply or sewer network. This is particularly relevant in areas where pipes are ageing, maintenance costs are rising, or continued operation no longer makes financial sense.

Independence reduces reliance on the grid

For households in isolated areas, the appeal is straightforward. The system reduces dependence on ageing pipes and distant treatment plants. Even if the public supply becomes unreliable, daily water use can continue.This independence also changes how infrastructure is valued. Instead of being a shared asset maintained by shrinking communities, water becomes something managed at the household level. For some local governments, this shift eases long-term financial pressure.

Backing comes from national concerns

The push has not come only from rural residents. Japan’s central ministries have supported research and deployment, recognising the scale of the challenge ahead. With climate pressures and demographic change overlapping, water security has become a planning issue rather than a background utility. Investment has followed. Billions of yen have gone into testing systems in real homes, not just labs. The goal is not full replacement of public networks but selective use where extension no longer makes sense.

A quieter change than expected

There is little spectacle in this transition. No large construction sites. No visible new landmarks. The systems sit out of sight, doing their work steadily. For now, they remain limited to certain areas. But their presence reflects a broader rethink. Instead of expanding infrastructure endlessly, Japan is exploring how to step back from it, carefully and without fuss.