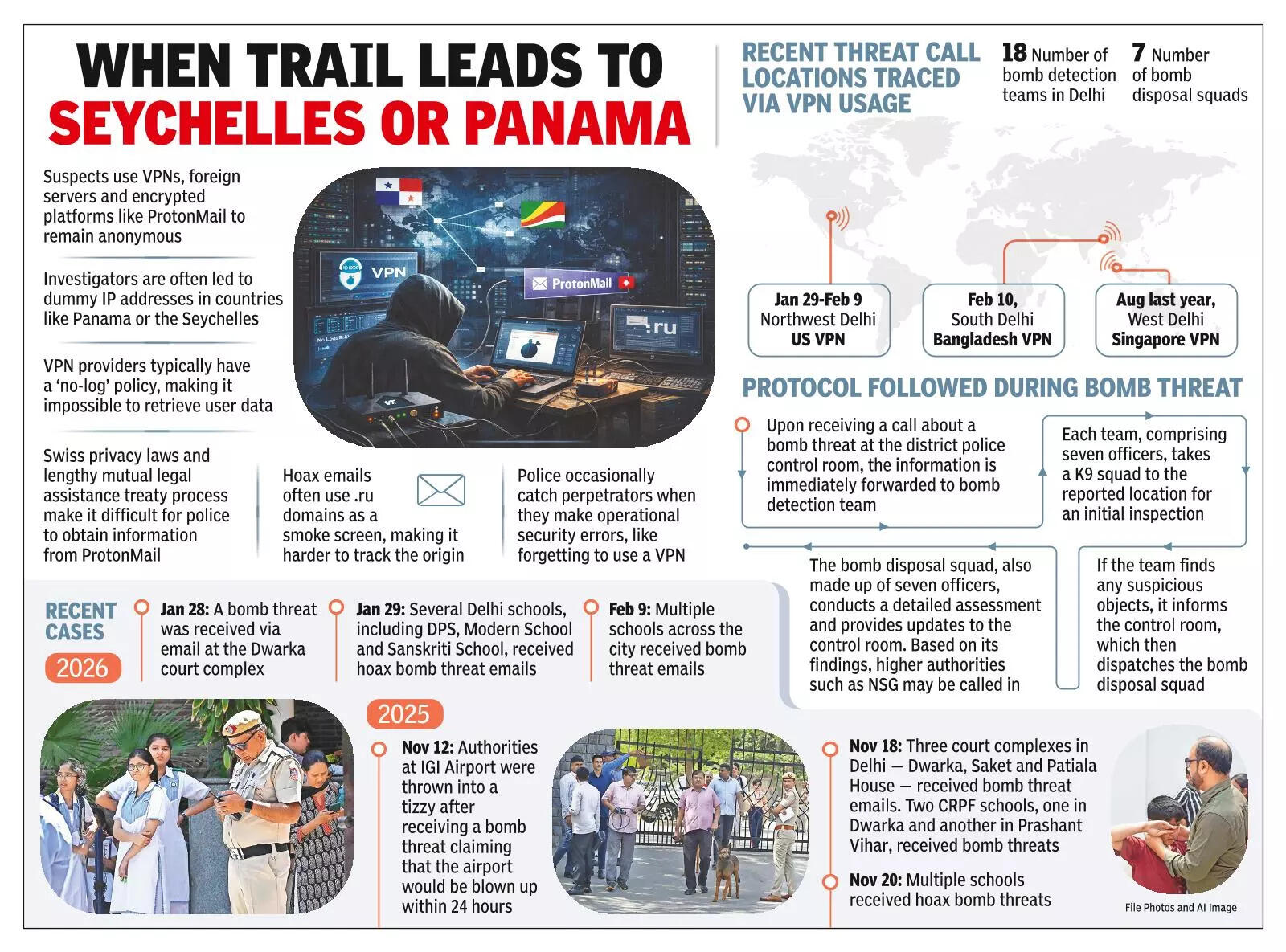

NEW DELHI: After some south Delhi schools received bomb hoaxes earlier this month, a technical probe led police to a virtual private network (VPN) service in Bangladesh. Days later, a spate of similar threats in northwest Delhi led them to a US-based VPN, while hoaxes reported in west Delhi schools a few months ago involved a Singapore-based VPN. However, even as police were busy writing to these networks to gather user details, they were flooded with more hoaxes.So, why is the law enforcement seemingly helpless in curbing this menace?

Blame It On Ironclad Privacy Of Swiss Servers, Geopolitical Opacity Of Foreign Domains, VPN Shields

When a threatening email lands in the inbox of a school in the city, the tactical response in the form of blaring sirens, evacuation of students and deployment of sniffer dogs and cops on the campuses is loud and swift.However, in tech dens of the police cyber cell, the reaction is quieter and the fightback uphill and borderline demoralising. For Delhi’s cyber-investigators, each hoax call represents a forensic dead end. Despite a string of such high-profile scares stretching into early 2026, the perpetrators remain digital ghosts. The inability to crack these cases isn’t due to a lack of manpower, but owing to unsurmountable technical hurdles: the ironclad privacy of Swiss servers, geopolitical opacity of foreign domains and multi-layered shields of VPNs.

When investigators attempt to ‘ping’ the origin of a threat, they aren’t led to a desktop in Delhi, but to a server in a jurisdiction like Panama or the Seychelles. Using VPN chains — routing a connection through multiple encrypted tunnels — the perpetrator ensures that the IP address visible to Delhi Police is a dummy. “The hoaxers hide their actual location in Delhi or elsewhere behind a series of encrypted ‘tunnels’. The IP address that police see may belong to a server in Austria, Singapore or Netherlands. To us, it is like chasing a shadow in a room full of mirrors; every time we think we have a lead, the trail bounces to another country,” said a cyber cell investigator. To get a real IP, police must request logs from a VPN provider. However, most premium services used by these actors operate on a strict no-log policy, meaning they do not store records of who use their services at a specific time. Simply put, there’s no data to be handed over to the cops. So, the trail doesn’t just go cold, it ceases to exist in the physical world.This wall of anonymity is reinforced by the choice of platform. In several high-profile waves of bomb threats, including the massive surge in hoaxes in May 2024 and the recent cases this month, the senders utilised Switzerland-based ProtonMail. Known for its militant commitment to privacy, ProtonMail uses end-to-end encryption, which even it can’t bypass, and does not require a phone number or personal details to create an account. From an investigative standpoint, this is a nightmare. Because the service is protected by Swiss privacy laws, Delhi Police can’t issue a standard search warrant. It must navigate the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty — a diplomatic marathon that requires proving ‘double criminality’ (that the act is a crime in both India and Switzerland). Even then, the most police may receive is basic metadata — like the time of the creation of an account — which is rarely enough to identify a sophisticated user who had signed up using a masked identity.The ‘Russian angle’ adds a final layer of complexity. Many hoax emails carry an ‘.ru’ suffix, often from services like mail.ru. Investigators frequently find that these domains are used as a tactical smokescreen.By the time a request for information moves through the bureaucratic channels of Interpol, the specific account is usually deleted and the logs are overwritten.Occasionally, police do catch a break — usually when a ‘copycat’ or a student makes a fundamental error in operational security, such as forgetting to turn on the VPN or using a personal recovery email. In late 2024, a student in Delhi was apprehended after sending a threat to his own school to avoid taking an an exam. He had forgotten to turn on his VPN, leaving his home IP address exposed.However, for the professional operators who target dozens of schools simultaneously, the global digital architecture is their greatest ally. The sheer volume of schools targeted — sometimes over 100 in a single morning — suggests a level of planning that involves scraping school databases from the dark web or using automated crawlers.So, as long as this infrastructure allows for perfect anonymity, all Delhi Police can do is operate within a reactive loop: evacuate students, search bags and declare hoaxes, while those behind the screen remain digital phantoms.