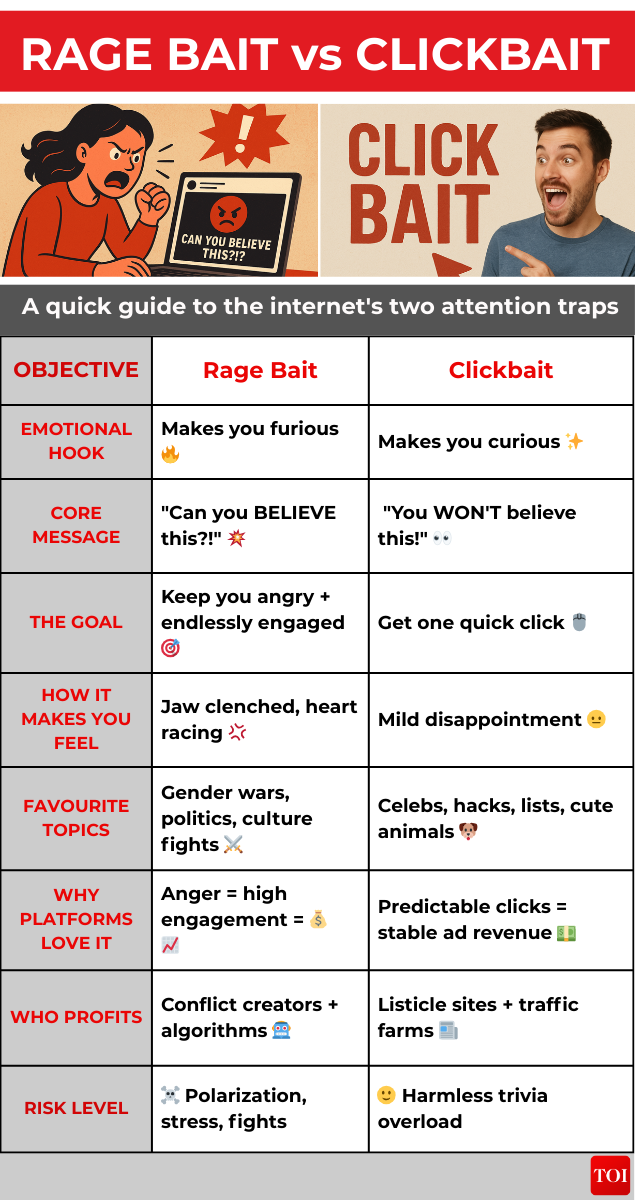

If you clicked on that headline, sorry — you’ve just been rage-baited.But that’s exactly what the platforms are doing, rage-baiting us into their content.That’s why ‘rage bait’ didn’t just trend this year, it muscled its way to Oxford’s Word of the Year for 2025, beating out terms like ‘aura farming’ and ‘biohack’ without even breaking a sweat.Rage bait is defined as “online content deliberately designed to elicit anger or outrage by being frustrating, provocative, or offensive, typically posted in order to increase traffic to or engagement with a particular web page or social media content”.Is it the same as clickbait? No.For instance, don’t read this article. It can make you angry — that would’ve been a classic clickbait headline. Tugging at curiosity, not outrage.

To understand this phenomenon, the TOI spoke with economic and psychological experts.

Is your ‘rage’ their product?

One of Oxford’s reasons for its selection of ‘rage bait’ for the top post was its threefold increase in the last 12 months. It also noted a “deeper shift” in “how we talk about attention — both how it is given and how it is sought after — engagement, and ethics online.”Does this mean that people’s ‘rage’ is the new kind of ‘attention’ that platforms like Instagram, Facebook, X and other social media websites are competing to get?“Anger holds economic value on digital platform,” said economics professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), Surya Bhushan, adding that “they drive higher engagement metrics — like comments, shares, and views — that platforms reward with algorithmic boosts and direct monetisation.” Does this mean that if you type “hasna tha kya” on someone’s standup reel, the algorithm will push more such reels just because you got angry?Content creator Divija Bhasin, who sees this dynamic in real time, however, disagreed. “I don’t think the algorithm pushes my content specifically to people who will be offended by it,” she said, who recently received extreme reactions on her “proud R-movement”, a reel she posted after getting repeated called the Hindi slur word.However, she further noted that while the algorithm doesn’t push content to offended people on purpose, it ends up sending it to people who will be offended by it because it cannot differentiate between “positive” interest shown vs “negative” interest shown.

Do you have the choice to not get ‘rage baited’?

“Anger-based content definitely undermines consumer autonomy,” said the JNU professor.He added that though the consumers have freedom to “scroll or engage”, the rage bait content “prioritises emotional hacks over rational choice”, calling it a way of “trapping users in addictive loops of reaction and counter reactions.”Herbert Marcuse, who was a part of the Frankfurt school of critical theory in the 20th century, helps make sense of this. He argued that capitalism creates choices that feel liberating but mostly serve the system.Can rage bait be classified as that? Are social media platforms built to reward it? Does it mean that when we think we’re choosing what to watch, we’re really choosing from options designed to keep us reacting, not thinking?

Are women at the receiving end of this rage?

Bhasin, who is also a psychotherapist, noted that since “misogynistic content is normalised” and doesn’t act as rage bait “for the average audience, especially men”, any kind of “progressive content” ends up being at the receiving end of their anger.“Misogynistic content is normalised and therefore doesn’t create a sense of rage for the average audience, especially men. So inevitably, any kind of progressive content is titled as rage bait because change from the norm will always evoke some level of denial in the viewer. It makes it seem like feminist content creators just want to make people angry,” she said.“When actually it is sad that misogynistic content does not make people angry. Misogynistic content is the real rage bait as it capitalises on the subjugation of women,” she added.Indian online spaces are increasingly turning into hotspots for gender-based violence, a report by international human-rights groups Equality Now and Breakthrough Trust found, as it went on to highlight the gaps in the legal framework.Bhasin cited concerns over the lax attitude of online platforms, saying that they “definitely capitalise on rage shown by men on purpose by not doing something to fix this problem.”“They are definitely aware of the kind of hate men spread on female influencers’ content. They are choosing to ignore it because it counts as time spent on the time, even if it is to hate on female influencers,” she said.